California’s Valley Oak is just coming into leaf in this locale. The branches of one of its magnificent specimens, undulating in the breeze, drape down and touch new green grass in the field.

That evening, the sight of a full moon in a striated sky comes as a shock. One has never seen a night sky quite like it. Around the moon is a halo reflecting the muted colors of a rainbow. Stars shine between the striations, and the earth seems to stand still.

That evening, the sight of a full moon in a striated sky comes as a shock. One has never seen a night sky quite like it. Around the moon is a halo reflecting the muted colors of a rainbow. Stars shine between the striations, and the earth seems to stand still.

It’s strange how intimately linked beauty is with timelessness and death—the actuality and essence of death, beyond the word, beyond physical death, without a trace of morbidity.

I’m not referring to death as we know and fear it, or even the cycles of life and death, but something immeasurable and unknowable, the ground of life and the universe itself. Calling that ‘death’ is like calling the Big Bang an explosion. Our minds cannot begin to encompass it, but can only fall silent and be aware of it to our capacity.

The actuality of death comes with the complete quieting of thought in attention. But one still has to walk through the door to enter the infinite dimension of death and creation—or perhaps more accurately, allow oneself to be carried into it. No healthy person wants to die, but there is nothing to actually fear about death.

When thought stops, time ends; when time ends, death beyond dying is; when death beyond dying is, creation and love flow into one.

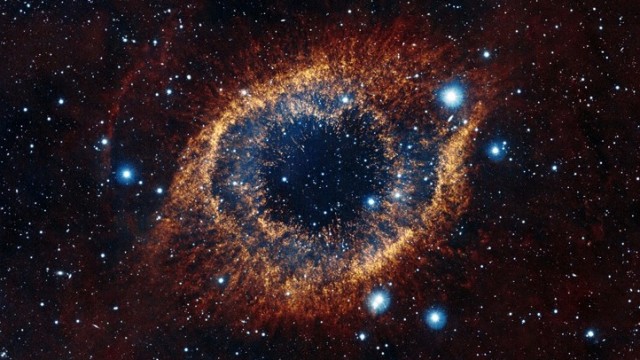

Time is a very strange thing. In astronomy, as most people know, distance is measured in units of time called light years. That’s the distance it takes light, which travels at about 186,000 miles per second, to go in one year, which works out to about 5.8 trillion miles. That’s why when astronomers look out they look back in time.

There are billions of galaxies of all shapes and sizes, each with billions of stars. Even observing the galaxy closest to us, Andromeda, which is about 2.5 light years away and the furthest object we can see with the naked eye, we are looking back in time two and half years. (Andromeda is near the constellation Cassiopeia, which is one of the prettiest words in the English language.)

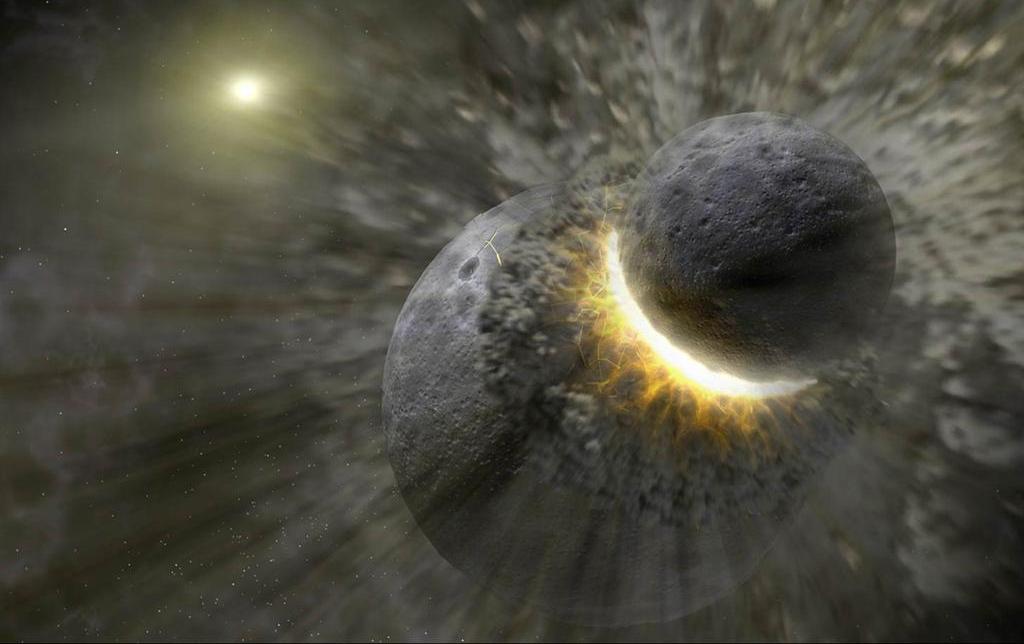

Andromeda will collide with the Milky Way in about a billion years, but don’t lose any sleep over it; we have a few more pressing concerns here on earth. And nothing is more pressing than understanding the nature of time and death, not just physically, as space-time, or when we kick off, when it will be too late, but psychologically, inwardly, now.

The earth is about 4.5 billion years old. You’ll often hear astronomers say nonsensical things like, ‘to reach us, the light from that galaxy began travelling 5 billion years ago.’ But the earth didn’t exist 5 billion years ago, so how can that be?

Using radio telescopes, astronomers have recently ‘seen’ back to trillionths of a second after the Big Bang, an instant after the beginning of the known universe, 13.8 billion years ago. They’ve confirmed Einstein’s hypothesized ‘gravity waves,’ which produced an instantaneous expansion, called ‘inflation,’ the moment after the universe was breeched.

As the report announcing this breakthrough in our understanding of the universe, and “one of the greatest  discoveries in the history of science” states: “The universe we see, extending 14 billion light-years in space with its hundreds of billions of galaxies, is only an infinitesimal patch in a larger cosmos whose extent, architecture and fate are unknowable…moreover, beyond our own universe there might be an endless number of other universes bubbling into frothy eternity.”

discoveries in the history of science” states: “The universe we see, extending 14 billion light-years in space with its hundreds of billions of galaxies, is only an infinitesimal patch in a larger cosmos whose extent, architecture and fate are unknowable…moreover, beyond our own universe there might be an endless number of other universes bubbling into frothy eternity.”

However nebulous both in fact and our field of vision, why can we see back in time at all, before the sun twinkle on, even before our galaxy existed? The first generation of galaxies has long since changed into something radically different, if they still exist at all.

Scientists have now probed back in time as far as they can go. There is nothing before the instantaneous inflation of the universe (or ‘multiverse’), since cosmic inflation precedes even the laws of physics, and ‘erases everything that came before it.’

Therefore in one sense even physical time is an illusion. Besides, all objects in the universe actually exist in the present only. Aren’t astronomers, looking out into the incomprehensible vastness of space, seeing everything as it was and everything as it is at the same time?

Be that as it may, psychological time is a complete illusion. Life and death are inseparable, though death is the ground of the universe, the infinite dimension beyond time. The eternal present is its portal. Entering its domain while fully alive, is there death at all?

Martin LeFevre