It’s a rather gloomy day, the first cloudy day in weeks. It’s my birthday and the atmosphere mirrors my mood. As one grows older birthdays tend to be tinged with sorrow, and even that dreadful thing, self-pity.

By the end of the hour beside the stream however, my mood has dissipated, replaced by a state of lightness and being. Walking back to the car, the weather has dramatically changed as well, with a setting sun illuminating fleecy clouds in the western sky. Beauty and newness again prevail.

By the end of the hour beside the stream however, my mood has dissipated, replaced by a state of lightness and being. Walking back to the car, the weather has dramatically changed as well, with a setting sun illuminating fleecy clouds in the western sky. Beauty and newness again prevail.

When time ends, death draws near without fear. One sees that it is always near, as close or even closer than life, but thought, by its very nature, pushes it away.

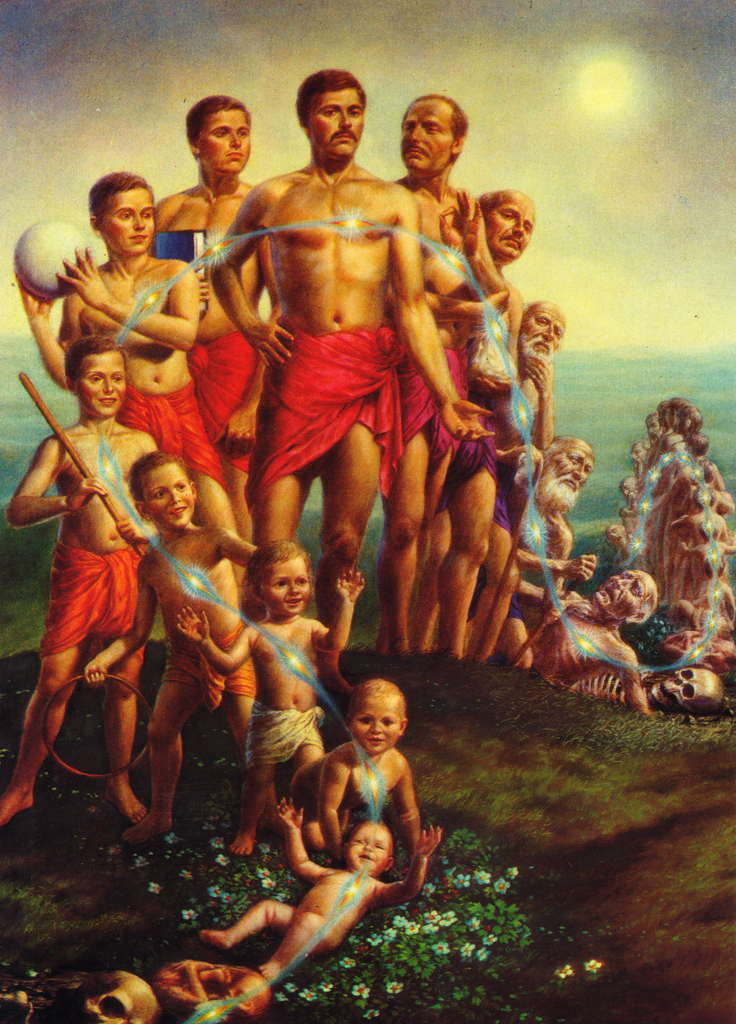

Western philosophy is wrong to dismiss reincarnation out of hand. I’ve come to feel that “reincarnation is a fact, but not the truth.”

That means traces of a person’s consciousness persist in human consciousness and return in some form, but the true intent in life is not to have to return and learn, but to unlearn and learn so that one doesn’t reincarnate, but incarnates.

When my mother, who was staunchly Catholic when I was young but had become disillusioned, unhappy and her worst self the last years of her life, died unexpectedly (though not in retrospect) at 84, I found myself pleading with God not to send her to the place beyond the reach of grace. And I didn’t even pray! As they say, there are no atheists in foxholes.

I don’t feel there is anything supernatural; there are only natural things that we don’t understand. What we call spirits are not supernatural, but some form of persistence and recycling within human consciousness.

I’ve also come to feel that hell is not a place of punishment, but a dimension in which the essence of a person is stuck, and has no chance of returning and learning and putting things right.

That’s what the expression, ‘where there’s life there’s hope’ really means. As long as we are alive physically, and more importantly inwardly, we can learn.

There comes a point however, where there are no more chances, not just because we physically die, but when we inwardly die and give up and no longer give a damn. Then we’re stuck in some interminable waiting area in human consciousness, unable to return until we’re freed through understanding and forgiveness by the living. Since that’s rare, and so many generations have been forgotten, hell is a very full place.

Be that as it may, my rare prayer during that moment of shock and grief seems to have worked. Not long ago, standing on the same spot in a meditative state where I last spoke to my mother, I had the distinct feeling that she’s already returned in some other body. It was no consolation.

The fear of death seems to be inherent in being human. If we remain with and question this fear however, we can see that it is not actually of death itself, but a fear of losing all continuity mixed with the idea of abyss.

Continuity is the most comforting illusion of all, whether of the spiritualist or materialist. And thought, that puny thing we mistake for actuality, inherently fears death, because without continuity, thought ceases.

Even children are sometimes ‘petrified by a void so vast that it cannot be contained within thought.’ Therein lies an essential clue to our existential dilemma: ‘cannot be contained within thought.’

In actuality, death is a fact as close as our cells, which are dying and being reborn every second, or our breathing, which recapitulates birth and death. What we fear is the idea of the ending of the self, and a self-projected void.

Regularly ending the continuity of thought and self (temporarily anyway, if that makes any sense), and communing with the actuality of death, I don’t fear death per se. One sees, when one is fully present, that death is merely a membrane, indistinguishable from life and love. What I fear is disease, poverty and isolation in old age. But that seems distinct from death, and more related to aging and society.

Words and concepts like abyss, void, horror and collapse don’t apply to the actuality of death, but to the projections of the self and its fear of ending, ceasing to be.

I don’t have a son, but I would feel like a philosophical failure if my son experienced the same fear of death that I did at his age. When a young son of a philosopher has the same childhood terror of death, then it means, sadly, that the philosopher has not understood this most important subject, and has passed his fear onto his son.

Spiritualist consolations have been replaced by materialist consolations. Materialists console themselves by saying things like, ‘the physical dimension of existence clearly persists beyond any biological threshold, as the material components of our bodies mix and mingle in different ways with the cosmos.’

Can anyone be certain that ‘the only truth is finite life in the here and now, which is destined to disappear forever in an instantaneous blackout?’ Can anyone categorically state that ‘eternal transcendence is nothing more than a comforting illusion?’

Reincarnation notwithstanding, death, whether we make a friend of it while fully alive, or fear and rationalize it while half alive, is synonymous the ending of continuity. That is the beauty of death and its potential as a portal, while fully alive, to higher states of being.

Immanence, which means ‘existing within,’ does not exclude or rule out transcendence. Indeed, immanence is the path to transcendence.

The materialist creed venerates thought and replicates fear. The journey of mystery on the other hand transcends the human mind and communes with the actuality of death, God and love, which turn out to be facets of the same thing.

Martin LeFevre