Deep beneath the earth, in a pool of super-chilled liquid xenon in an abandoned gold mine in the Black Hills of South Dakota, scientists are looking for ‘dark matter’. But they aren’t finding any. Perhaps it’s because the dark matter is to be found in human consciousness, not under the Black Hills.

With unintended irony, America’s leading newspaper editorially intones: “In the tale we tell about everything we know, scientists have now brought us to the edge of the deep, dark woods.”

With unintended irony, America’s leading newspaper editorially intones: “In the tale we tell about everything we know, scientists have now brought us to the edge of the deep, dark woods.”

They mean to say that the inner earth search is at the cutting edge of man’s expanding knowledge in the Stygian darkness of the cosmic void. But void and vacuity exist only within man, and that’s the last place scientists are looking.

I’m not really trying to conflate unknown matter in the universe with unrecognized matter in human consciousness. But it is hard to know what people commenting on science are talking about, when scientists admittedly don’t know what they’re talking about.

Science is a story based on testable observations, but it’s still a story, “a tale we tell about everything we know.” More accurately, science is a story about the meaning and place of knowledge. It’s not the truth (the word itself, ‘truth,’ sounds quaint these days), or even observable facts. And dark matter and dark energy themselves don’t even rise to the level of theory, but are phrases spun from what we think we know about the universe, and don’t know about ourselves.

Scientists might point out that the existence of black holes was just a theory, postulated by Einstein with his space and mind-bending insights into space-time, before black holes were observed at the center of the Milky Way and every other known galaxy.

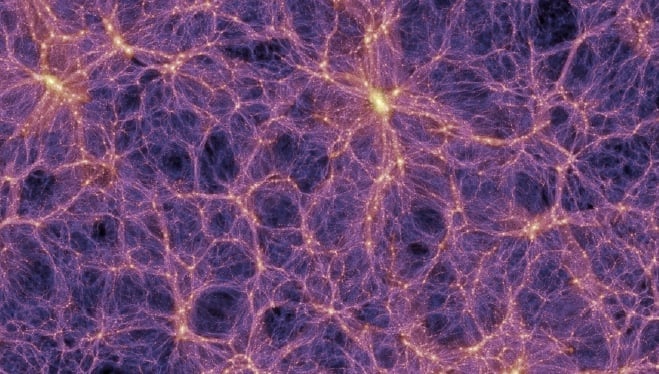

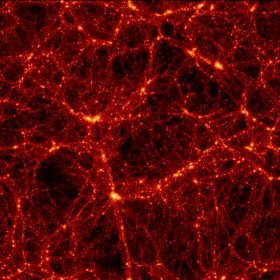

But the hypothesis of black holes arising from new insights into the nature and operation of the universe is one thing. Terms like ‘dark matter’ and ‘dark energy’ invented to fill in huge gaps in knowledge are another. (Dark matter is guesstimated to account for 25 percent of everything; dark energy for 70 percent; and galaxies, stars, planets and people a mere 5 percent.)

In the short but messy history of man, ‘the deep, dark woods’ stand in for all manner of goblins and gargoyles. Never mind that when our species initially came down from the trees and walked on two feet, they returned to the trees for safety at night. Once we became savanna hunters after being savanna scavengers, the woods/jungle/forest became a metaphor not just for the hidden dangers in  nature, but for the malevolence humans generate and project.

nature, but for the malevolence humans generate and project.

For an alternate view of nature, we have only to turn to an article from the day before the silly New York Times editorial, “High-Caliber Cosmic Nothingness.” It was entitled, “Far Off Planets Like the Earth Dot the Galaxy.” In it, we learn that the “cosmos has gotten increasingly friendly and fecund-looking over the last 20 years.”

Geoffrey Marcy of the University of California, Berkeley, who is involved in the search for earth-like planets orbiting relatively nearby stars, said, “This is the most important work I’ve ever been involved with. This is it. Are there inhabitable Earths out there?” Given recent findings by the Kepler orbiting telescope (which now has a crippled pointing system), and estimations of the frequency of terrestrial type planets extrapolated from the data so far, he added, “I’m feeling a little tingly.” (Insert stereotypical joke about Californians here if you wish.)

So which is it—a Stygian darkness of the deep, dark woods, or a consciousness-friendly cosmos? You can’t have it both ways, nor expect science to resolve what it cannot resolve—the way one sees nature and humankind’s place in it.

Our worldviews turn on a core premise about nature and man. Either nature is hostile and man creates order out of chaos; or nature is order and harmony (even as it is completely indifferent to us personally), and man generates chaos.

Two streams are converging (or colliding) in human consciousness at present, and the question is, can something new emerge? The first stream is the ancient human attitude and fear of wilderness, now extended, as man has ‘conquered’ nature on earth, to the cosmos.

The second, for which denial still rules, is the increasing and pressing reality of the darkness in human consciousness, and the fact that human consciousness is the maker of darkness.

That’s what makes the search for ‘dark matter’ rather hilarious. It isn’t that some vast quantity of unknown matter don’t exist in the universe; it’s that calling it dark, while remaining willfully oblivious to the unseen darkness within and around us is the height of folly.

There’s a saying: “Bring forth what is within you, and what you bring forth will save you; do not bring forth what is within you, and what you do not bring forth will destroy you.”

Martin LeFevre