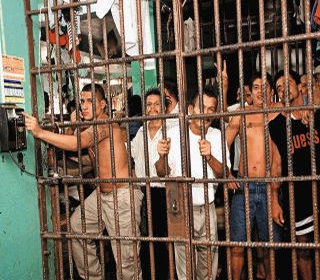

Costa Rica News – Prison overcrowding is a widespread problem in Latin America, primarily because of harsh drug-sentencing laws and inadequate budgets, but Costa Rica may be setting a useful example for dealing with it. In most countries, guards control the perimeter, but groups of prisoners or criminal gangs organize and control life inside the prison compound. Rehabilitation and re-integration programs are limited.

Not surprisingly, there is little political leadership for prison reform; the issue wins few points with the general public. Even dramatic events – like prison riots in Venezuela or prison fires in which hundreds of young men die as in Honduras – don’t generate interest in prison reform. A key component of the criminal justice system – as a deterrent, a punishment, and as a provider of rehabilitation and reintegration services that will reduce recidivism – the prisons are often neglected.

Not surprisingly, there is little political leadership for prison reform; the issue wins few points with the general public. Even dramatic events – like prison riots in Venezuela or prison fires in which hundreds of young men die as in Honduras – don’t generate interest in prison reform. A key component of the criminal justice system – as a deterrent, a punishment, and as a provider of rehabilitation and reintegration services that will reduce recidivism – the prisons are often neglected.

While Costa Rica faces growing drug-related problems, a multi-country analysis by the Washington Office on Latin America of persistent criminal justice and prison problems in Latin America – aimed at identifying strategic solutions – indicates that the country stands out as having undertaken at least modest reforms of its prisons to prevent them from becoming the breeding grounds for increasingly hardened criminals and gangs.

Prison conditions in Costa Rica have not been among the worst in Latin America, although the US State Department said in its Human Rights Report for 2013 report that they were “harsh” and that “overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, difficulties obtaining medical care, and violence among prisoners remained serious problems.”

Until very recently, when new drug sentencing laws and tough anti-crime measures pushed the prison population up, the system generally did not exceed capacity. Even today, the system is at 140 percent of capacity – far less than the 200-300 percent seen in other countries. Prison conditions also seem less abusive than those seen in other countries. An external oversight body was created to protect the rights of prisoners.

Moreover, the government, with support from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), is reaching out to local businesses to support vocational training programs for inmates.

This process has been driven by reformers inside the government and prison system, in contrast to most reforms elsewhere in the hemisphere driven by international donors. This is a rare example of how reformers inside and outside the system worked to achieve institutional changes that increase citizen security while respecting human rights.

In this case, long-standing mid-level and senior staff of the penitentiary system, with the support of successive Ministers of Justice appointed by President Laura Chinchilla, played a key role in resisting pressures from legislators who want to toughen sentencing, which would increase prison populations. They have advocated measures to ease overcrowding and ensure proportionality in sentencing. At the same time, they have also used the IDB loan to both defend and expand the rehabilitation and re-insertion programs in the prison system.

Every country’s situation is unique, and Costa Rica has advantages — a relatively low crime rate, a relatively strong state structure, a relatively well-established respect for the rule of law – that others lack, but San José has shown that reform in this difficult, politically sensitive area is possible.

Geoff Thale and Adriana Beltran, of the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), recently led a small delegation to visit Costa Rican prisons.