“Ignorance is our natural state; it is a product of the way the mind works.” Statements like that, proffered by cognitive scientists Philip Fernbach and Steven Sloman in the New York Times, demonstrate that cognitive science has become the phrenology of our day.

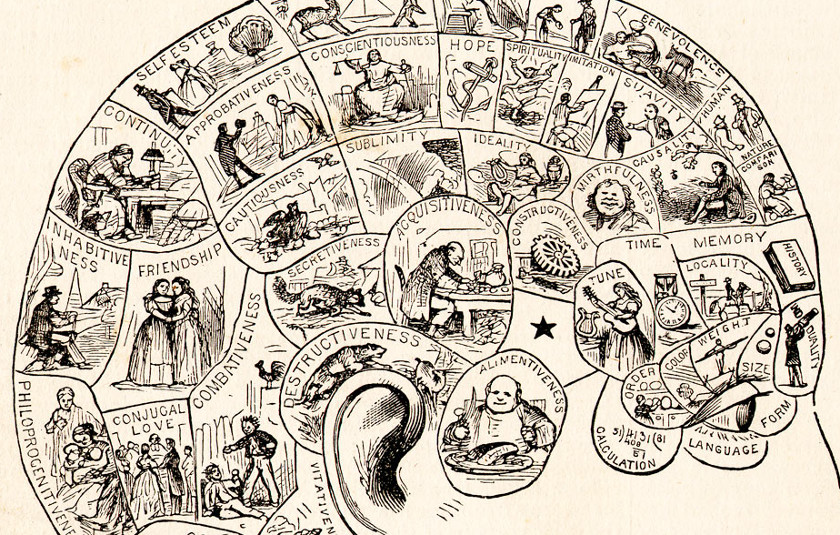

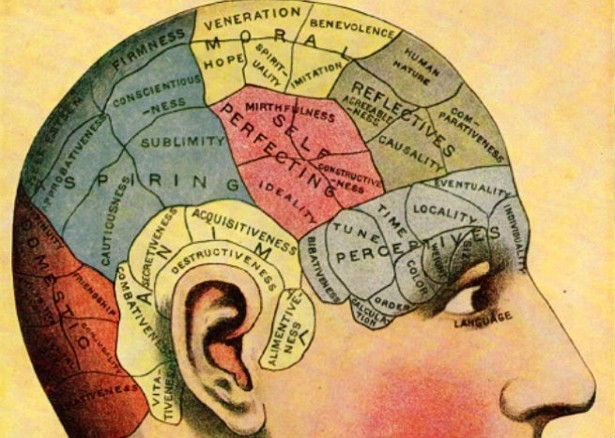

Phrenology was a pseudoscience in the early 19th century that focused on measurements of the human skull. It purported to link specific bumps and nodes with traits and characteristics of the mind and personality. Like cognitive science today, phrenology was quite influential with psychiatry.

Phrenology was a pseudoscience in the early 19th century that focused on measurements of the human skull. It purported to link specific bumps and nodes with traits and characteristics of the mind and personality. Like cognitive science today, phrenology was quite influential with psychiatry.

Developed by German physician Franz Gall in 1796, the “assumption [of phrenology] that character, thoughts, and emotions are located in specific parts of the brain is considered an important historical advance toward neuropsychology.”

Cognitive science is “the study of thought, learning, and mental organization, which draws on aspects of psychology, linguistics, philosophy, and computer modeling.” It’s a mishmash that has led to all manner of unexamined premises.

The idea of the historical advance in knowledge of the mind is itself questionable, since we are no closer to understanding ourselves as humans than we were during Dr. Gall’s day. In fact, I would argue that we are further from genuine understanding of the relationship mind and brain, since the technologies of science confer an even greater hubris on cognitive scientists and their ilk.

“The secret to our success as a species is our ability to jointly pursue complex goals by dividing cognitive labor…each of us knows only a little bit, but together we can achieve remarkable feats.” Making authoritative statements such as these is nothing more than confused philosophy posing as clear science.

Fernbach and Sloman demonstrate a remarkable ignorance of their own, especially with regard to the nature of knowledge and the two completely different types of learning (cumulative and non-accumulative).

They make the human brain identical with mental capacity and knowledge, both individual and collective. Most of all, they fail to ask the right questions. For example, what is the relationship between the brain, thought and awareness? Is there learning that is not based on knowledge and experience?

By individualizing mental capability and collectivizing knowledge, and speaking in terms of “dividing cognitive labor,” they miss both the forest and the trees.

Implicitly placing the highest value on mental capability is a mistake of the highest order. It demonstrates a willful ignorance of the nature and uses of thought and knowledge. Even worse, it willfully fails to understand the difference between separation and division.

Separation is the core feature of thought. We humans evolved the ability to consciously “remove and make ready for use,” the literal definition of separation. We did not evolve, and cannot evolve, the insight that it’s an existential mistake to carry separation over into the psychological realm. Doing so, the Promethean gift of separation became increasingly divisive and fragmentary.

Division of labor refers to the separation of functions, not the “division of cognitive labor.” The authors display an astounding lack of self-knowing, and try to cover their ignorance with a sleight of hand by making “division of cognitive labor” the basis of “collaborating with another individual to achieve a goal.”

Fernbach and Sloman are psychologists. But they completely neglect to mention how psychological division gives rise to greed, gross economic disparity, identification with particular groups–a particularly egregious error given the resurgence of the tribalism of nationalism. Not to mention the fragmentation of nature, and war. As such, they are guilty of malpractice.

At the core of this bad science and worse philosophy are assumptions (unexamined premises) regarding the nature of knowledge and our capacity to perceive truth.

By conflating knowledge, truth and understanding, and claiming, with authoritarian certainty, that our individual capacity for perceiving and understanding truth is a function of collective knowledge, Fernbach and Sloman damage the human prospect.

“On their own, individuals are not well equipped to separate fact from fiction, and they never will be.”

Frankly, that isn’t simply mistaken; it’s pernicious claptrap, no better than reading bumps on the skull and making solemn pronouncements about the character and traits of a person.

The perception of what is, and the understanding of ever-changing truth is not a function of knowledge at all; it’s a function of direct and holistic perception. “Dividing cognitive labor” distracts and detracts. That is the path to individual and collective ignorance, not individual and shared understanding.

It’s not only possible, it is essential to question and observe without giving primacy to knowledge and experience. Knowledge has its place obviously, but it is not first. Experience, the subconscious form of knowledge, can be rational or irrational, but it prevents direct perception and insight in the individual.

This is the philosophy of discredited experts, the very people who paved the way for mob rule in America and Europe through their hubris. They have no bottom, since they still believe they are leading the people out of the morass. They offer nothing but more of the same division and darkness.

Martin LeFevre

Link: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/03/opinion/sunday/why-we-believe-obvious-untruths.html