The upper branches of a large, leafless sycamore hold the last golden rays of the sun. In the deep shade below, the silvery water gently undulates downstream through banks still brown during this winter’s drought with last summer’s grass. That which is beyond words or description comes as gently as the current.

The mystery and reverence of deep dusk dispel the remnants of time. For a few minutes at least, the mind is free of thought and the heart is free of sorrow. Neither thought nor sorrow can continue when the movement of psychological time ends, and vice versa.

The mystery and reverence of deep dusk dispel the remnants of time. For a few minutes at least, the mind is free of thought and the heart is free of sorrow. Neither thought nor sorrow can continue when the movement of psychological time ends, and vice versa.

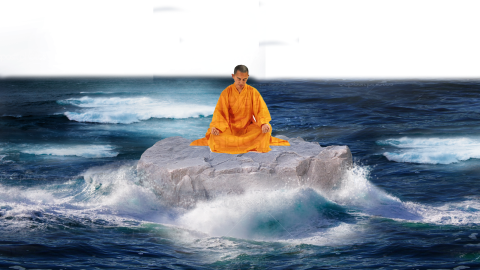

It grows dark, but I don’t want to leave the small sanctuary meditation has made, and reenter the world and content-consciousness. One has to reenter the world, but can one remain beyond the stream of content-consciousness?

Most people rarely if ever know a moment when psychological time ends. How then can it be conveyed, much become the rule in human consciousness?

Though I’m not an adherent, Buddhism has a term called ‘stream-winner.’ It means a person who has eradicated the first three ‘fetters,’ a funny word that’s synonymous with shackles. (When was the last time you heard or read someone say, ‘He’s fettered to his job?’)

Anyway, the first three fetters are: the belief that the self actually exists; excessive doubt (what we call cynicism); and clinging to rites and rituals. It’s interesting to note that transplanted Buddhism seems to elevate all three of these fetters in North America, but that’s another issue.)

The first and last fetters are quite apparent to me, and have been since I was a young man. The second I still grapple with, to the extent that I sometimes doubt that anything but negation in meditation in the individual exists, that intelligence is not operating at all in human consciousness, at present anyway. Is it?

Curiously, I don’t doubt the validity of the sacredness that comes during deeper meditations, even if it seems, only a few hours later, light years away. The question I keep returning to is: Why does psychological time remain the default position of the brain, when one repeatedly experiences the timeless state of being?

In short, I’m much more interested in stream leaving than stream winning. To irrevocably leave the stream means to me not returning to the state of becoming, of thinking in terms of later or eventually, of being finished with even the subtlest pursuit of ideas of what one should or could be.

me not returning to the state of becoming, of thinking in terms of later or eventually, of being finished with even the subtlest pursuit of ideas of what one should or could be.

Sometimes it seems like intense meditations act like powerful lasers, piercing all the way through the dense material of content-consciousness, illuminating a dimension without shadow, of being without becoming. But then the material of the past, of memory and association, of thought and fear seeps back in, and the opening is closed, only to reopen again with the next complete meditation.

It sounds rather Sisyphean, like the mythic fellow who was condemned to push a boulder up a hill, only to have it roll back down and have to push it up again, over and over. But without seeking it, or even seeing it except in retrospect, it feels like one’s own consciousness is becoming more and more porous, and that human consciousness, despite appearances to the contrary, is as well. (Pang of doubt inserts itself here.)

Living completely in the here and now has become fashionable at a superficial level, while at the same time gotten a bad rap in terms of becoming a success in this horrid culture. “Countless books and feel-good movies extol the virtue of living in the here and now, and people who control their impulses don’t live in the moment,” two prominent writers on the elements of success recently intoned. That neatly expresses a fabrication wrapped in a half-truth.

In point of fact, people who truly live in the moment do understand the imperative of restraint, which requires self-knowing and non-reactiveness, as opposed to control, which involves suppression and will. Living in the moment doesn’t mean living in terms of gratifying and pleasuring the self, but ending the separation of self and illusion of time.

Deferring gratification (aka self-control) may generate success and wealth in society’s terms, but in the process it has produced a soulless culture. Most then react to the deadness by ‘living in the here and now,’ which usually means grabbing as much pleasure as you can right now. They’re two sides of the same coin, neither having anything to do with inward growth and happiness.

Living in terms of right now is completely unrelated to living in the here and now.

Martin LeFevre