There’s a junior high school within sight of where I take my sittings a few times a week beside the creek that runs along the edge of town. I often see young teens walking home along the bike path running parallel to the stream 100 meters behind me. Lately someone has been building little stone stacks near my spot.

Called stupas, or chortens in Tibet, little stone stacks have become common calling cards in America and Europe. What they mean in the West is anyone’s guess, but I think they express a yearning for connection to nature and others in a deeper way.

Called stupas, or chortens in Tibet, little stone stacks have become common calling cards in America and Europe. What they mean in the West is anyone’s guess, but I think they express a yearning for connection to nature and others in a deeper way.

Like anything and almost everything in an age where ‘trending now’ has the highest value, chortens have become a fad, and are showing up everywhere, to the chagrin of those seeking solitude in the mountains or valleys.

Anyway, after whoever erects the little stone stacks (an endeavor requiring some patience) near where I take my meditation, someone comes along and knocks them down.

This funny little drama has been going on for some weeks. I’ve never seen either the creators or the destroyers, but my best guess is that junior high school girls, seeing me meditating under the old sycamore, set the stones up, and junior high boys, seeing the girls build them, come along and kick them down.

To my mind, meditation is not a ‘practice,’ much less technique, method or discipline. I simply enjoy being in nature, and watching the movement of thought and emotion in the mirror of nature. It requires no effort or goal; indeed, when effort and goal creep into meditation, it ceases being meditation.

The poppies along the little creek (which is flowing far more copiously at present than the main stream through town does during the summer) are in full flower. Bouquets of brilliant orange flowers surround me, and with spring at the top of the swing, the sun is warm right down to the horizon.

Besides the intrinsic sensory delight of looking at the green fields and hills and listening to the rippling stream, passive watchfulness orders the mind, cleanses the heart, restores balance, and brings intimations or more of the ineffable sacredness within and behind nature and the cosmos.

However, yesterday’s experience of the Brahman, God, or whatever you want to call it is the greatest impediment to experiencing it today.

Rather than seeing meditation as passive communion with God, I see it as drinking from the wellspring of the infinite unknown. Paradoxically, passive watchfulness leads to being intensely inwardly alive, while being active often leads to passive participation in deadening socialization.

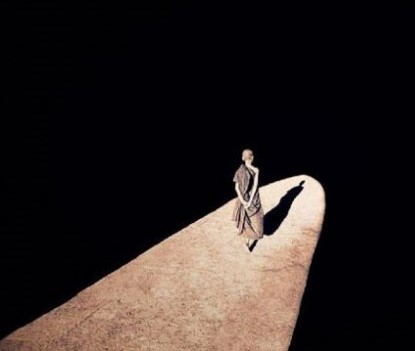

So freedom as I understand it means non-volitionally and spontaneously leaving the dimension of the known, and drinking from the infinite wellspring of the unknown. Leaving the known still seems fearful sometimes, but when I actually do, one is complete and completely at peace.

Experience is the known. And we almost always live in terms of experience, which is psychological memory. Can it really end, and can one live another way altogether?

The map denies the territory, and the territory of the unknown is accessible only through the portal of the present. That requires inclusive, undirected and intense attention—not mantras, concentrating on your breath, and all that nonsense.

How many people actually leave the known on a regular basis? One in a million? More like one in 100 million.

If the intrinsic intent of cosmic and terrestrial evolution is to evolve brains capable of conscious communion with the infinite unknown (God if you will), why is it so rare in this world and on this planet?

When I leave the stream, almost always in a meditative state in which the mind is completely quiet and the heart completely open to the beauty of the earth, I ask that the consecration of the meditation that day protect the place.

I also ask that everyone who comes down to the creek feel something of the essence one has awakened here, feels it to the extent they can receive it at present. Perhaps the girls do. Harder to reach boys.

Martin LeFevre