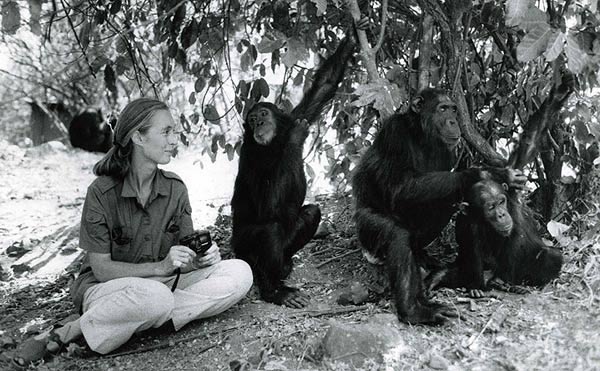

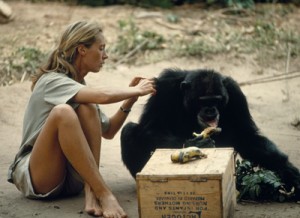

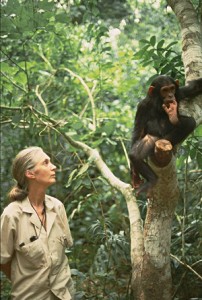

Jane Goodall, longtime observer and friend of chimpanzees in Tanzania, said recently that like humans, chimps “have a dark, brutal side to their nature.” Maybe they can teach us something.

Goodall was horrified to observe chimps in the Gombe Reserve prosecuting a well-planned war against a neighboring troop. Not only were ambushes carried out, but an entire group was exterminated. Sound familiar?

Goodall was horrified to observe chimps in the Gombe Reserve prosecuting a well-planned war against a neighboring troop. Not only were ambushes carried out, but an entire group was exterminated. Sound familiar?

Swing over to Alan Greenspan, the guru of the global financial system during the Clinton and Bush Administrations, and the goat of its collapse since. He made one of his characteristically surface-clear/profoundly opaque comments recently. “Unless somebody can find a way to change human nature, we will have more crises.”

We call it ‘human nature,’ but it isn’t actually nature, just a big wrinkle in evolution that all species in whom symbolic thought evolves must sort out. Not that chimpanzees have the defining characteristic of humans, self-awareness, although the mirror test indicates they have awareness of self. Then again, most humans aren’t self-aware either.

The mirror test is when you introduce a chimp, a gorilla, and an orangutan to a mirror, and let them become familiar with looking at their image in it. Then the mirror is removed and big red spot is painted in the foreheads of each animal. When the mirror is re-introduced only chimps touch the spot, indicating that they have a self-image. This is also what passes for self-awareness in humans—having an image of ourselves.

Obviously, chimps can’t invent technology or devise plans as well as humans can, nor can they concoct belief systems and accrete complex cultural traditions to the degree of Homo sapiens.

‘Planet of the Apes’ notwithstanding, perhaps they could take our place in another few million years if we wiped ourselves out. But then, they would be faced with the same psychological, philosophical and spiritual crisis we are at present. Would they also then talk about the unchangeability of ‘chimp nature?’

The fashionable practice of blurring the line between chimps (and animals in general) and humans, as Jane Goodall, one of the leading proponents of this philosophical stance has done, throws no light on the human condition.

It’s simply not enough to say, as Goodall does, “chimpanzees show far more frequently the tendencies of compassion, empathy, and  love than violence and brutality.” The same can be said of humans with regard to our families and groups with which we identify.

love than violence and brutality.” The same can be said of humans with regard to our families and groups with which we identify.

After saying that “chimpanzees teach us that we’re part of the animal kingdom,” Goodall was asked, what is the essential difference between animals and humans? “Animals by and large are not destroying their environments, although some of them would if they could,” she replied. That’s classic anthropomorphizing.

Nonetheless, Goodall asked the central question: “How is this most intellectual of species that’s ever walked the planet, how is it that we’re destroying our only home?”

Her answer just begs the question: “It’s because of the disconnect between the clever brain, and the seat of love and compassion, the human heart.” OK, but how did that disconnect originate, what sustains it, and what heals it?

Chimpanzees, with their occasional wars and genocides, are the best evidence on this planet, other than humans, that the evolution of ‘higher thought’ carries with it profoundly divisive and destructive tendencies.

A fresh approach to the old problem of nature or nurture is necessary. One basic question is: What is the difference between conditioning in humans, and conditioning in chimps and our other primate cousins. Perhaps what we call human nature is simply a discordant mixture of dominant conditioning (or, to use the more popular term, ‘socialization’) and recessive instinct.

Be that as it may, to grow beyond the level of brainy chimps, we have to have a core insight into ‘higher thought,’ and through passive observation regularly quiet the psychological (as opposed to utilitarian) movement of thought.

Liberation is a break (temporary or irrevocable) from the current of conditioning and socialization into which we’re born, and to which the vast majority of people consciously or subconsciously resign. Liberation is the regular release, however briefly, into the infinite space and depth of insight and learning. It’s predicated on continually unlearning what was infixed upon us as children, and entrenched as worldview, experience and habit as adults.

Whether the transmutation from humans to human beings happens in the foreseeable future or in the unforeseeable future, one has to have faith that it will happen, because there is no choice. Ending humankind’s destruction of the earth, and erosion of our spiritual potential, depends on questioning fixed assumptions about human nature, the world and oneself.

There is another dimension of being, as far beyond where the human species is at present as chimpanzees are from us. And though it’s a leap, it really isn’t that far.

Martin LeFevre