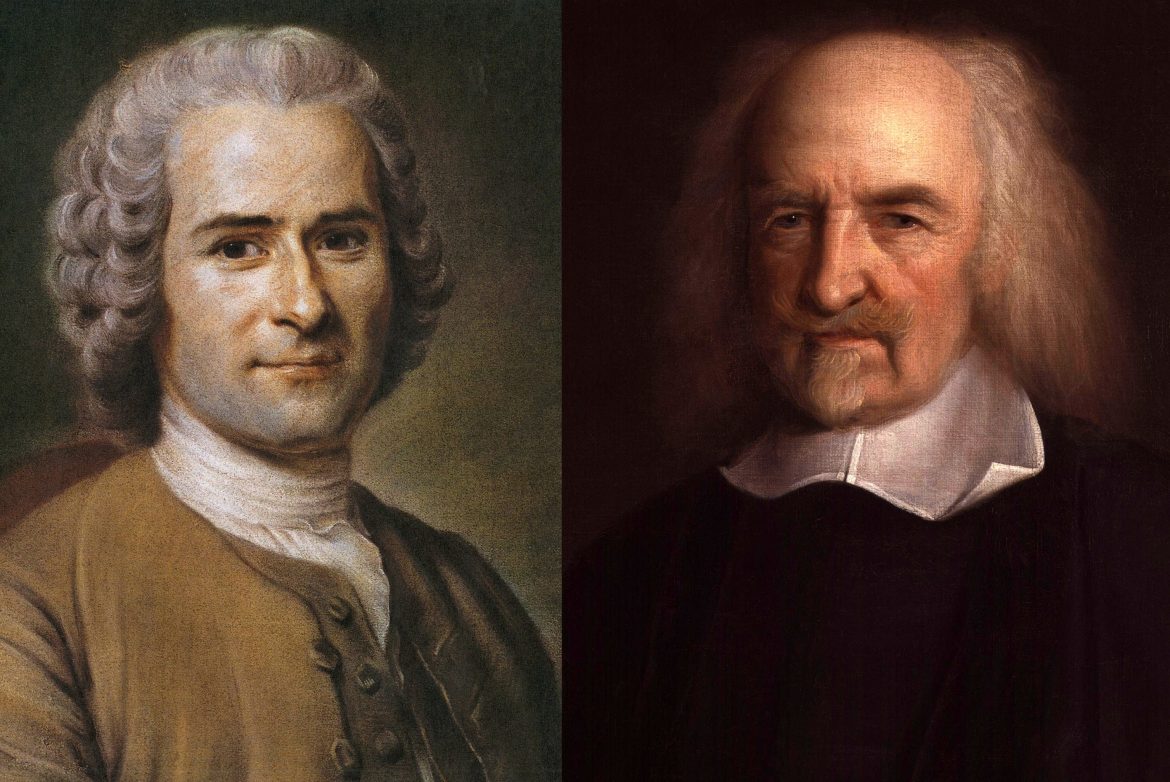

Are you a Hobbesian or a Rousseauian? Most people’s core worldview falls into one philosophical camp or the other, which usually determines where we fall on the political spectrum.

Thomas Hobbes was a 17th century philosopher who argued that deference to authority, and faith in strong leaders, the law and civic institutions are necessary to save us from ourselves. Otherwise, in his view, humans would continually fight over power and resources.

Jean-Jacque Rousseau was an 18th century philosopher who argued the opposite, believing that humans start out innocent and get corrupted by society. Private ownership of land was anathema to him, and he famously said, “You are lost if you forget that the fruits of the earth belong to all and the earth to no one!”

Hobbes was a social Darwinian over two centuries before Darwin was born. He is considered the “father of political philosophy,” which is to say, he poured the philosophical foundation for the system that is crumbling around us today.

As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy states, “Hobbes is famous for ‘social contract theory,’ the method of justifying political principles or arrangements by appeal to the agreement that would be made among rational, free and equal persons.”

“He is infamous for having used the social contract method to arrive at the astonishing conclusion that we ought to submit to the authority of an absolute—undivided and unlimited—sovereign power.”

Rousseau, on the other hand, is considered the father (again in the sexist language and practice of philosophy) of the Romantic Movement. Rousseau’s saw “philosophers as the post-hoc rationalizers of self-interest, as apologists for various forms of tyranny, and as playing a role in the alienation of the modern individual from humanity’s natural impulse to compassion.”

In short, Hobbes “tooth and claw” view of nature is the philosophy of plutocrats and autocrats on the right, whereas Rousseau’s notion that “nothing is so gentle as man in his primitive state” often underlies people’s views on the left.

For myself, I see these as two sides of the same debased coin. On one hand, humans are only immutably self-centered and self-interested if we accept ourselves and resign to humanity as such. On the other hand, the notion of “humanity’s natural impulse to compassion” is poppycock.

Hobbes was correct in saying that in the “state of nature,” human life was “nasty, brutish and short.” But Rousseau was correct in saying that “everything degenerates in the hands of man.”

Ironically, Hobbes is seen as a philosopher of hope, since “though violence is in our genes, we go to extraordinary lengths to contain it.” Whereas Rousseau was “consistently and overwhelmingly pessimistic that humanity will escape from a dystopia of alienation, oppression and unfreedom.”

We live in the self-fulfilling prophecy of a Hobbesian world. That’s demonstrated by an incredibly wrongheaded article in the Telegraph about a month before Donald Trump was elected, entitled, “Science shows Thomas Hobbes was right—which is why the Right-wing rule the Earth.”

Such a view fails to make the first distinction of any intelligent human being, which is between nature and human nature. Both questions have to be left open. What nature essentially is, and what humans essentially are, are unanswerable questions with certainty and finality.

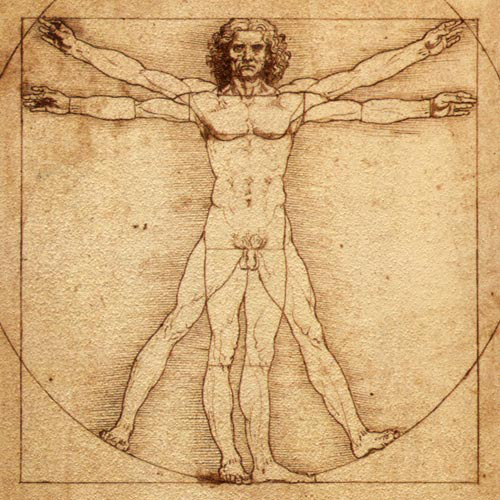

That said, the evolution of “fully modern humans” produced a qualitatively different kind of creature. Philosophers acknowledged this fact long before Hobbes and Rousseau put their own spins on the old conundrum of ‘man’s place in nature.’ The attempt to scientize human behavior, epitomized by the fad of evolutionary psychology and the “science shows” mentality, is the mark of our absurd age.

Traditional Christian theology both recognized and believed it resolved what used to be called “the riddle of man” by positing special creation, adding insult to injury by proclaiming, “man is made in the image of God.” Even as a boy I  thought it must be one miserable God if that’s true.

thought it must be one miserable God if that’s true.

My philosophical obsession as a young man was in this area, what’s called “theories of human nature.” The basic direction of humankind is to separate, divide and increasingly fragment the earth and ourselves, whereas all other life unfolds in seamless wholeness. I had to find out how evolution could produce a creature, so-called Homo sapiens sapiens (“wise wise humans” no less) which operate antithetically to nature’s essential movement.

If nature is essentially a movement of seamless wholeness unfolding over eons, and wholeness is essentially good, how could nature evolve such a creature as man, which is increasingly, if not inherently fragmented and corrupt?

Put another way, why do humans, a single, supposedly sapient species, have the capability of dominating the planet to the extent that we’re bringing about the Sixth Mass Extinction in the entire history of life on Earth?

I found out I feel, but then saw that the explanation doesn’t change the explained, beginning with myself.

However it does provide a good philosophical foundation, though as David Bohm, the man Einstein called his spiritual and intellectual son wisely advised me, “Don’t make another philosophical system out of it.”

Martin LeFevre