Many years ago a Soviet cosmonaut, Yuri Romanenko, expressed the American ‘work ethic’ when he was asked about the beauty of the earth from space. He said, “Basically you work.”

“You realize that you are looking at all this beauty with a professional eye: You note the transparency of the atmosphere and its meteorological structure, the traces of the currents in the oceans, accumulations of plankton, concentrations of industrial pollution, interesting geological structures, areas where forest fires had raged, stretches of saline soil; you identify, photograph, jot things down; basically you work.

“You realize that you are looking at all this beauty with a professional eye: You note the transparency of the atmosphere and its meteorological structure, the traces of the currents in the oceans, accumulations of plankton, concentrations of industrial pollution, interesting geological structures, areas where forest fires had raged, stretches of saline soil; you identify, photograph, jot things down; basically you work.

In not answering the question about perceiving the beauty of the earth from space, but putting it in quotidian terms of detailed work, this cosmonaut brings two questions into relief: What attitude or approach allows the emotional perception of beauty? And what is the right attitude and approach to work?

Taking the second question first, most people work because they have to earn a living. But even those who don’t have to worry about making a living (either because they have skills that are in demand or because they have another source of income), doing what one loves is rare. Once in a while you’ll hear someone say, “I can’t believe they pay me for doing what I love to do,” but even scientists, cosmonauts and artists usually have other motivations for the work they do.

Whether Yuri loved his work in space or not I don’t know, but an additional statement he made indicates that he often found his work to be a bore and a chore, as most people do. “Sometimes time flies, and sometimes it almost stands still; like Einstein said, everything is relative.”

That sounds quite Russian–giving the logic of familiar work even in the most unfamiliar of circumstances, ending with a dead-end as certain as the Soviet Union. Though he was in space, he ironically expressed an almost universal misconception of Einstein’s work, which demonstrated exactly the opposite of “everything is relative.”

Einstein discovered that space and time couldn’t be separated, not that ‘everything is relative.’ That’s a comparative mentality, not a mind that sees what is. And this is where the question of beauty and the question of work overlap.

To perceive beauty one must have a relationship to what is, and not be coming from thought and knowledge. And a  relationship to what is, while negating the known (experience and the familiar), and holding knowledge in abeyance, is a precursor to the perception of truth.

relationship to what is, while negating the known (experience and the familiar), and holding knowledge in abeyance, is a precursor to the perception of truth.

Two of the best jobs I’ve ever had were being a janitor, once in a school, and once in a bank, each for about a year. It was honest work, and afforded the opportunity to study and write once the toilets and rooms were cleaned.

The president of the bank saw me changing light bulbs in the hall one day and called me into his office. “What are you doing?” he asked. Feigning obtuseness, I said, ‘changing light bulbs.’

“No, I mean why are you working here? I’ve noticed you, and I’m sure you could be successful in business.” Having sensed that’s where he was coming from, I replied, with perhaps a little too much of the assurance of youth, that I was a philosopher and writer. Since this society gave no support to either, I was fine being a janitor for the time being because it allowed me to do what I loved to do. He shook his head and never spoke to me again.

That was in the mid-70’s, when America was a much more diverse and livable place than the cultural hellhole it has become. And there’s still no place for philosophers or writers, except as they echo some stale narrative in spent academia or declining newspapers.

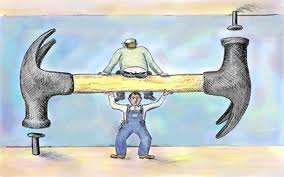

Work has become problematic, to say the least. Innovation, production and labor are global, but the political narrative and mentality are still nationalistic. Jobs, like companies, cross increasingly irrelevant borders, even as governments spend more and more money on ‘defense.’

And jobs aren’t just threatened by cheap labor in Asia or wherever. As computers and robotics replace more and more types of jobs, the very meaning of work has to be redefined. Globalization is demanding not that we fit into archaic notions of work and success, but that we reinvent work and living. In the process, we’ll reinvent society.

One doesn’t need to be recognized for one’s work, but it is necessary to be acknowledged for the work one does. Of course, some of the best work in history went unrecognized and unacknowledged in someone’s lifetime, but that doesn’t make it right.

To understand the work that is beyond the prison of the mundane, indeed beyond the prison of time (whether it passes slowly or relatively quickly), one has to consider beauty. What the Russian cosmonaut articulated is how not to see beauty, how to be blind to beauty by putting knowledge ahead of perception.

To understand the work that is beyond the prison of the mundane, indeed beyond the prison of time (whether it passes slowly or relatively quickly), one has to consider beauty. What the Russian cosmonaut articulated is how not to see beauty, how to be blind to beauty by putting knowledge ahead of perception.

On one hand, meditating in space is probably easier, because one is continually reminded of the wholeness of earth. But on the other hand it’s no doubt harder, because one has only a portal view of nature, and all other sensory inputs are man-made—sounds, smells and touch.

Creativity always begins with sensory input—the actual sounds, sights and smells of the present. They are fairly easily distinguishable from one’s thoughts, memories and associations, but it is very difficult to remain with the distinction, and hold both movements in awareness without any interference.

Seeing the whole and awakening meditative states are the wellspring of work that’s creative and intrinsically rewarding. That’s called doing one’s spadework.

What we think is never what is. Yet most people don’t even hold space in their minds for seeing what is, which requires an attitude of doubt and skepticism about what one thinks and believes.

Can the work of the individual within society fit within the work of the transmutation of man of the ages?

Of course it can. The question is: Will humans continue to put time before timelessness, expertise before wholeness, knowledge before beauty, and reason before insight and understanding?

Martin LeFevre