Everyone seemed to be out on a warmish Saturday afternoon at the peak of autumn in northern California. Yet there were no crowds and there was no crowding at the entrance to Upper Park.

When I reached the little lake outside town that forms the opening to and anchors the canyon, and saw the gate closed because of recent rains, I didn’t expect to find a place to park in the usually jammed lot on a weekend. But there was a spot, and I walked down the hill to the streamside path.

When I reached the little lake outside town that forms the opening to and anchors the canyon, and saw the gate closed because of recent rains, I didn’t expect to find a place to park in the usually jammed lot on a weekend. But there was a spot, and I walked down the hill to the streamside path.

I passed a quintessential American family—mother, father, two small children and a dog. The young father seemed surprised that I smiled and said hello, and he responded enthusiastically. It always amazes me how such a small thing can make a difference in one’s and others’ days.

Despite many rocks in the path, I strode strongly and easily beside the swollen stream, passing only a few more people, though most of the spots along the creek were occupied. The trees were resplendent in full fall color, and every turn in the trail brought a new delight.

I walked about a half hour before coming to a good spot for a meditation in the mild November sun. It afforded a quarter-mile view upstream, a serenading cascade downstream, and a view of the path as it descended a slope, marked by a large, dead oak at the top.

It was a place in relatively untrammeled nature where I could see and be seen, and that seemed fitting on this day. Passive and intense watchfulness yielded a meditative state, with meditation beginning, as always, by negating the observer. Awareness can and must grow quicker than thought’s ability to separate itself from itself, which is essentially what the observer is.

As meditation deepened, it struck me once again that the human brain is, potentially, a vehicle for awareness of the sacred, and the sacredness of awareness. For that to be however, the mind-as-thought must be completely still in unforced, undivided attention to its movement.

It also struck me that you can live in the world without the timeless, but one cannot live without the timeless in one’s life and be a human being. There is no use for the timeless, nothing to gain from it and no success or failure in it. But without it, life becomes as barren as the backside of the moon.

Walking back, a mother, two sons and dog stood on a huge log along a rise beside the path, watching a paraglider hang seemingly motionless in front of the cliffs. It was a tremendous sight. He kept circling and didn’t appear to be losing elevation, obviously catching updrafts known only to hawks and vultures on what felt like a windless day at streamside.

I stopped and we talked a bit about the grace and beauty, as well as danger of paragliding, sharing a moment with a stranger in that open and free way Americans have at their best.

I felt, as I strode away, that I was given an answer to my question of the relationship between experiencing timelessness in meditation and living in the world of time. For a few minutes there was no duality, no conundrum. With insight and understanding, one is like a paraglider, without the separation between humans and nature, just a single graceful movement.

It’s strange how even the smartest, best educated, and most experienced people have to believe humankind is heading in essentially the right direction, and that the revolution in consciousness essential to change the disastrous course of man has already begun.

When the obvious truth is pointed out to them, they pretend to reconsider, but because their real motivation is not to be disturbed, they default to the ever-soothing bromide of relativism, saying, ‘each to their own truth.’

So the intent and capacity to see things as they are together, much less discover the truth together, eludes them. Desperately seeking a silver lining rather than face the gathering darkness and basic direction of man, even so-called philosophers say inane things like, “Anxiety is the motor that drives the engine of freedom.”

They of all people should know better, but they don’t know how to delve and ignite insight any more than Joe six-pack or Jane box-wine. And when the gatekeepers ignore and try to refute a nation’s best,

they should not be surprised when they get the worst.

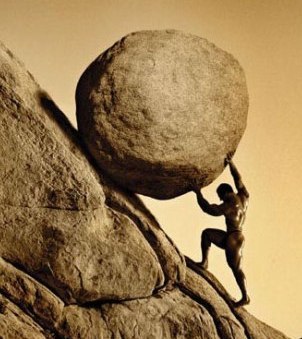

The task before us is Herculean, not Sisyphean. The myth of Sisyphus, endlessly returning to the bottom of the hill to push his rock back up again, is a metaphor for hopelessness and existential dread of the world, and life.

On the other hand Hercules, in holding open the ‘Gates of Hercules’ (in ancient times, the promontories that flank the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar), is a metaphor for the potential strength, discovery and greatness of human beings.

Martin LeFevre