The animal spotted me jogging up the path in the park. It stopped and turned about 100 meters ahead, and then again at 75 meters. It was the size and shape of a dog, but moved like a cat.

I saw it scoot into the brush around the turn, and didn’t think I’d be able to confirm its identity. But as I made the turn and looked to the right, there it was, just 10 meters away standing on a log looking at me. A coyote!

I saw it scoot into the brush around the turn, and didn’t think I’d be able to confirm its identity. But as I made the turn and looked to the right, there it was, just 10 meters away standing on a log looking at me. A coyote!

In 15 years, it’s the first coyote I’ve seen in Lower Park, a narrow strip of land that follows the creek and runs through this college town of around 100,000 people.

Having had a sitting that ignited a meditative state, one’s senses were sharp and attuned, and the mind deeply quiet and present. In that state I found myself standing face to face with a healthy coyote, in the prime of its life, its gray bushy tail held out straight, its ears up, and its eyes piercingly alert.

Its curiosity and intelligence were palpable. We stood motionless for some timeless seconds staring at each other. The species barrier did not seem to exist. We were simply two beings looking at each other–an animal in its natural state, and a human in a meditative state, both in the middle of town.

Then something happened that felt quite natural at the moment, but later seemed extraordinary. For a moment, the mirroring was so clear that all separation between the human being and the coyote disappeared altogether. For a second or two, it felt like one was looking at the man through the coyote’s eyes.

Did I imagine it? No, because thought was not operating and the mind was deeply quiet. Then what happened?

Biologists have an expression: Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. It means that each stage of evolution contains the previous stages in an individual’s gestational development. In other words with mammals, including humans, all previous evolution is enfolded and replicated in our growth in the womb.

previous stages in an individual’s gestational development. In other words with mammals, including humans, all previous evolution is enfolded and replicated in our growth in the womb.

So in a very real sense, we were once coyotes, and still are in some portion of our brains. Therefore it’s possible to see with a coyote’s eyes, and not just figuratively. But attention must be acute thought completely still.

A cyclist came up riding the path 100 meters away. Though she was out of the coyote’s line of sight, when I turned back the animal was gone. The tear in time and space had closed, and the gulf between the human species and animal world instantly returned. One was thrust back into the world of cyclists, runners, and dogs.

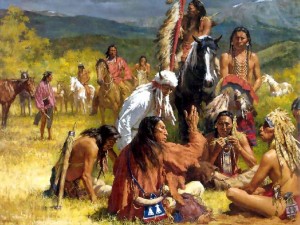

Native Americans often spoke about such experiences, and their myths flowed from them. The coyote figures prominently in these myths. For some tribes he was mainly seen as a trickster and fool, for others a transformer and creative force.

According to Crow and other Great Plains Indians of pre-Columbian America, the coyote was second only to the Spirit Chief itself in its powers of creation. “Old Man Coyote took up a handful of mud and out of it made people.” The Miwok of the Central Valley and western slopes of the Sierra Nevada in California saw the coyote as an essential force in the creation of the earth.

The Crow said, “Old Man Coyote named buffalo, deer, elk, antelopes, and bear. And all these came into being.” This reflects humility about the power of language and thought, which evolution conferred on us as humans. At one level, naming things makes them real and comprehensible for humans. But at another, to name something is to separate it from its environment. So by saying Old Man Coyote named the animals, an insight into the essential inseparability of life was retained for indigenous people.

All myths are really about humans and their place in nature, as well as our powers to create and destroy in the world. Humans projected into the coyote their own imaginative power, a power, for good or ill. (Mostly for ill now, since man is causing the extinction of many species and bringing the earth to the brink of ecological collapse.)

All myths are really about humans and their place in nature, as well as our powers to create and destroy in the world. Humans projected into the coyote their own imaginative power, a power, for good or ill. (Mostly for ill now, since man is causing the extinction of many species and bringing the earth to the brink of ecological collapse.)

Whether as creator, trickster, or culture hero, the coyote spirit in Native American mythology stands in for the core contradiction of the human mind in nature. Thought names, separates, and builds worlds, but it cannot create nature, or anything else. Thought can only be creative when it’s subordinated to insight and intelligence, never when it’s primary. Making thought primary, even and perhaps especially as science, is what makes man destructive.

Ruled by the mind, tens of thousands of years of human history are coming to a head. When we lived close to nature, and our technology was primitive, there were reminders of our relationship to nature, and brakes on our destructiveness. But now all brakes and bets are off.

There is no evolution of culture and consciousness. We have remained psychologically unchanged as humans since modern man emerged from the mists of East Africa about 100,000 years ago. Whenever and wherever that cognitive breakthrough and leap occurred, all humans thereafter were fully equipped to build cathedrals, create art, and replicate thought with computers. Technology has ‘evolved,’ but man has not.

Therefore, whereas man’s knowledge has grown exponentially, man’s mind and heart are now shrinking, perhaps in inverse proportion. There is a real and present danger of humankind becoming a shadow of what we once were, much less what we could be.

The divisions of tribalism as ‘my family and my country;’ the immaturities of belief and organized religion; and the unmoored and decontextualized traditions of cultures and civilizations have become dead weights dragging man down and drowning the human spirit.

Insight, the greatest gift man possesses, must renew the brain, or the old mind will destroy the earth, and with it the human spiritual potential. Can the duality, destructiveness, and arrogance of thought give way now to stillness, insight, and humility?

Martin LeFevre