Having witnessed an instance of shocking abuse by a nun upon a friend in Catholic school in the 8th grade, I began to question, observe and research the religion in which I was raised.

Though much of my research was subconscious, I learned a great deal about the Church. By my senior year, my mind was made up. So I came down one Sunday when it was still a mortal sin to miss Mass that day, and I announced to my shocked parents that I wasn’t going to Mass that day or ever again.

I didn’t leave because of what Pope Benedict called “the filth of the Church” (pedophilia, corruption, and cover-up), but because I saw that the framework is false, even as some elements (and people) within it are true.

I never looked back, and never considered joining another organized religion. Looking back now, I realize that I didn’t become truly religious until I left the Catholic Church.

Without seeking a substitute, or any spiritual experience, ‘mystical experiences’ began about a year after I left the Church. I put mystical experiences in air quotes because they are neither mystical nor experiences to my mind, but rather unexplained phenomena and transitory spiritual events.

The breakthrough occurrence, which has remained the cornerstone of meditation for almost 50 years, occurred while watching a robin on the grass in my parent’s backyard.

For some weeks I had noticed weeks that there was always an observer standing apart from what was being observed, even within oneself. So I started asking: What is this observer?

The question must have been germinating, because suddenly, without consciously thinking about it that day, there was an explosion of insight. It was completely beyond words, but the closest I can put in words is: The observer is essentially a trick of thought, separating itself from the environment and itself.

The robin burst into color, vibrancy and being, and the emotional realization of its aliveness extended to every living creature on earth. Psychological separation, I saw beyond words, was the “original sin,” the ongoing existential mistake embedded in what we blindly and blithely call human nature.

I hadn’t thought of Jesus for 20 years, until a brush with death about 25 years ago, and an encounter with an elderly Chinese woman as I was recovering. She strongly evoked the spirit of both the Buddha and Jesus, though the Jesus that she evinced bore little resemblance to the Christ of the Church.

In the Catholic Church, the priest is an intermediary to Jesus and God, and he is given the power to forgive sins in the confessional. In the incarnation of Jesus through the Chinese woman (who had come to America after she escaped the Cultural Revolution), there was no intermediation. I saw that forgiveness must flow from the individual’s heart, and I immediately forgave my mother, who had wronged me on my last visit.

Jesus said, “If you forgive you will be forgiven.” As Stephen Mitchell points out in “The Gospel According to Jesus,” “Jesus is teaching us forgiveness; it is never a question of his forgiving sins.”

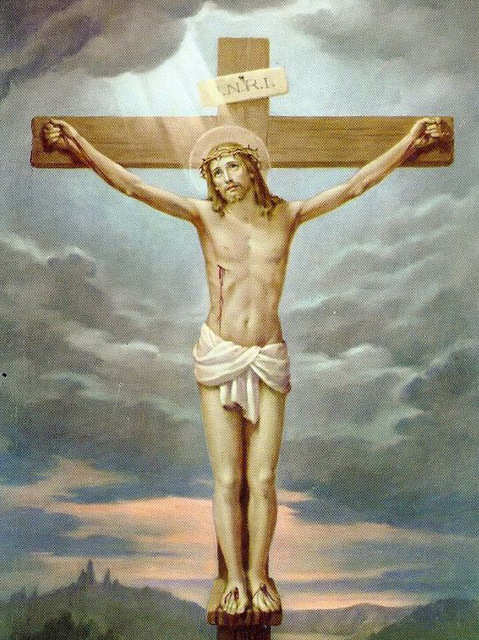

After that encounter I began to make a distinction between Jesus and Christ, and Jesus’ mission and his crucifixion. I feel the central mistake of Christianity is conflating all four.

The word “Christ” comes from ‘christos,’ a Greek word meaning “anointed.” Beyond becoming synonymous with Jesus of Nazareth however, Christ has come to mean Logos, “the ideal truth that comes as a divine manifestation of God to destroy incarnate error.” Jesus certainly didn’t achieve that.

So who, or more accurately, what was Jesus? Jesus was an illumined human being that walked the earth, taught and tried to show people a different way to live.

Christ, from a mystical point of view, is immanent in all energy and matter in nature and the universe, and potentially, in human beings.

I feel that the actual Jesus would find the basic tenet of Christianity—the idea that “Jesus is God”—an utter blasphemy. No matter how perfect, or how imbued with “divine spirit” a human being is, he or she is not and cannot be God.

That belief arose because Jesus followers, both immediately after and in the centuries following his death, could not come to terms with the failure of his mission, which is what the crucifixion actually was.

That isn’t to say Jesus himself failed. He didn’t lose faith, even on the cross, in God and humanity. But his mission failed, and perhaps Jesus himself didn’t understand why.

Rather than face the failure of Jesus’ mission, which would mean taking it back on themselves, Christians since Constantine began to believe that his crucifixion was the fulfillment of the messianic prophecies of the Old Testament. Upon that falsehood, the Catholic Church and Christianity were formed.

Whatever our religious background, most people feel that humankind is meant to live in harmony with and on the Earth.

Can we as individuals and a species make the turn toward inward and ecological harmony at this time? Can a revolution in the human heart ignite, manifest and change the disastrous course of humankind now?

Martin LeFevre

Lefevremartin77 at gmailcom