Many of the movies that Hollywood has churned out in the last 20 years are based on the premise that evil is interesting while good is boring. That’s hard to argue against since it has obviously paid handsomely. But the truth is, as a pundit recently wrote, “At this point in the Trump era, it’s a constant challenge not to let oneself be bored by evil.”

Looking beyond the parlous borders of the United States, a small news item jumps out at the reader from man’s atavistic past: “On Monday evening, in a brutal hand-to-hand battle, Chinese soldiers killed at least 20 Indian soldiers with wooden staves and nail-studded clubs, in the severest escalation of the dispute on the Sino-Indian frontier in decades.”

Looking up the word ‘atavistic,’ the online dictionary leads with this trenchant example of its usage: “Our atavistic fear of one another, our tendency to extreme violence and destruction, particularly under the stresses of conflict, the ease with which we seem to lose our own humanity, and with that, all those higher noble qualities we all possess – mercy, compassion, forgiveness, our love for each other as members of the human race.”

Throwbacks to tribalism/nationalism and pre-Bronze Age hand-to-hand combat notwithstanding, a non-theological, non-psychologized philosophy of evil is clearly called for. But what would such a philosophy look like, and how would it help anyone but the debating societies of academic philosophers?

Even before World War II was over, Aldous Huxley excoriated “the utterance of speech-making politicians, writing, “In half an hour’s yelling from a platform it is intellectually impossible for even the most scrupulous man to tell the delicately complex truth about any of the major issues of political and economic life.”

I wouldn’t quibble with that, except to point out that Lincoln made a pretty fair stab at it. Nonetheless, despite or because of the abundance of such fecal froth as primal skirmishes over obscure borders in the high desert between China and India, or children mercilessly caged on the frontier between the developed and underdeveloped world that the US-Mexican border represents, the age-old problem of evil demands an adequate response.

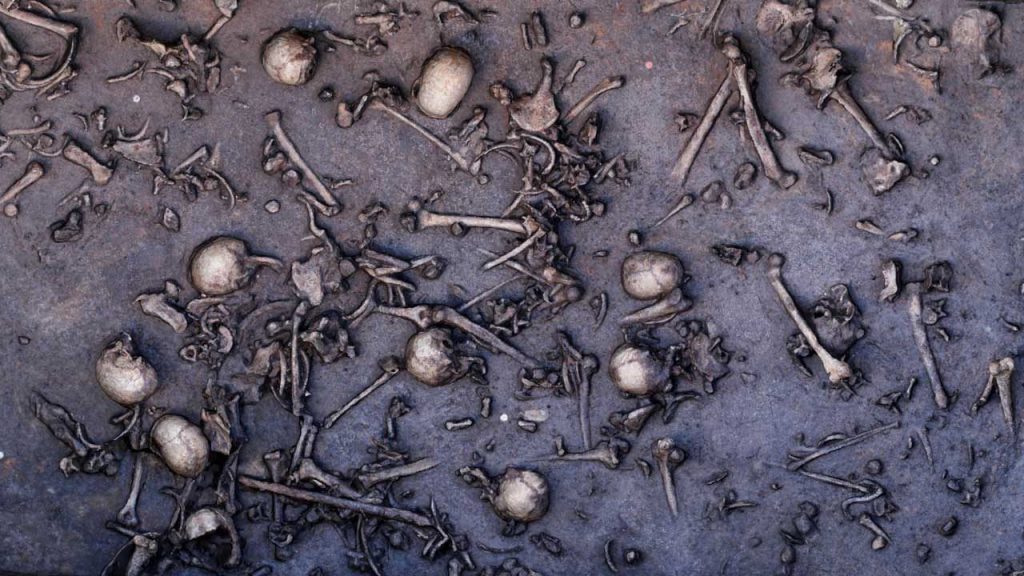

The present world almost makes one long for the good old days of the stable Cold War, when, as my philosopher-friend in Costa Rica says, the concern was only “who had their fingers on the red buttons.” Whether we’re talking about sharpened sticks or the still ominously futuristic looking SR-71 “Blackbird,” mass murder and the preparations for mass murder by one tribe against another haven’t essentially changed in untold thousands of years.

American commentators wring their hands and gnash their teeth about how President Trump believes his “personal interest is the national interest,” but at bottom, self-centeredness and nationalism have the same source—the division between me and you, us and them.

Even so, that doesn’t come close to giving an adequate, non-theologized, non-psychologized philosophy of evil.

The obvious first question is: What is evil? Though this certainly doesn’t cover it, one can say evil is an egregious eruption of hate and violence in an individual or a people.

The next question is: Does evil have collective intentionality in human consciousness? This is the sticking point for philosophy, psychology, as well as most decent people. Everyone that is, except religionists, who believe that good and evil preceded man and are in cosmic, supernatural conflict.

Dismissing the latter as juvenile and clearly unhelpful in the history of humanity, we’re left with the fact that eruptions of collective darkness happen all the time. Something larger than the individual, or even a bigly group of people, can burst into the open and take over a person, or a nation. Evil is first an inner phenomenon before it is an outward manifestation.

For example, despite exhaustive investigation, the FBI found “no single or clear motivating factor” in the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino slaughter of 58 concertgoers in Las Vegas on October 1, 2017, the worst mass shooting in the land of mass shootings.

And despite decades of analysis and thousands of books, there has been no adequate explanation for the eruption of evil in the people who gave the world Beethoven and Goethe, which produced tens of millions of deaths in World War II, as well as the Holocaust.

Laying my philosophical cards on the table, my core premise is that other than practical and scientific knowledge, the content of human consciousness, individually and collectively, inexorably tends toward accumulating dark matter, which is now leaving less and less space within, suffocating hearts and shrinking minds.

So what we call evil is a conscious or unconscious intentionality of malevolence and chaos that erupts in an individual or a people out of the unaddressed dark matter of innumerable generations.

The cipher that sprayed machine-gun fire down on the throng in Las Vegas was not motivated by solely individualistic factors. In his utter weakness of character and complete absence of compassion, he became a conduit for the vast content of darkness in this culture.

Evil is man-made, not cosmically generated. There are life hating self-hating things in human consciousness that want the destruction of the human spirit and spiritual potential. Violence and chaos are means to that end.

The best Hollywood depiction that I’ve seen of how evil operates is the movie, “Fallen,” with Denzel Washington. Though falling back into a theological framework, it depicts how easily evil can flow into and through inwardly dead people.

For decent, reasonable people, unlike the faceless, face-maskless mob attending Trump’s rally in Tulsa today, losing sight of the culture and world we live in has become analogous to losing sight of the Covid-19 pandemic—one risks being infected by the real or metaphorical virus.

The antidote to evil is awareness and a scrupulous inner life. And an inner life requires being very honest with oneself on a daily basis. In short, when I feel hate, I must see it as it is without excuse or blame, face it, and remain with it.

The ancient saying true: “Bring forth what is within you, and what you bring forth will save you. Do not bring forth what is within you, and what you do not bring forth will destroy you.”

Martin LeFevre