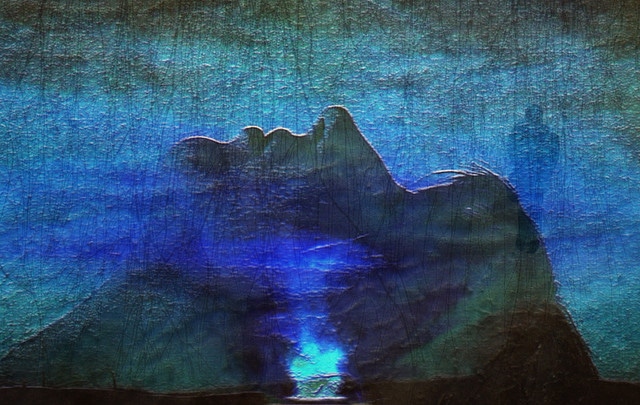

“Manshape, that shone sheer off, disseveral, a star,

death blots black out;

Nor mark is any of him at all so stark

but vastness blurs and time beats level.

Away grief’s grasping, joyless days, dejection.

Across my foundering deck shone

a beacon, an eternal beam.

Gerard Manley Hopkins

While still in my teens, a question seized me that took 15 years to resolve to my satisfaction. The question was this: Given that nature unfolds in seamless wholeness, how did nature evolve man, who is generating increasing fragmentation and destroying the Earth?

I talked to every philosopher I could from the West and the East, from the dean of Stanford’s philosophy department to Gandhi’s grandson, who was teaching philosophy in San Francisco when I lived there. No one could give me an insight into the great anomaly between humans and nature—what used to be called “the riddle of man.”

Science has tried to resolve the dilemma in the last three decades by blurring the difference, by giving evidence that human behaviors have their antecedents and parallels in the natural world. That hasn’t cut it.

The attempt to enfold human evolution within primate and mammalian evolution flows from a philosophical premise—that humans aren’t actually separate from nature. That’s undeniably true, but it begs the question: why do we think, feel and act as though we are separate?

Besides implicitly demonstrating that philosophy trumps science, this attempt at blurring and blending humans and nature has utterly failed to halt man’s destructiveness. Climate change and the Sixth Extinction have continued unabated.

When I realized that no one had adequately explained the disjunction between the way humans and the rest of nature function, I began to ask the questions alone, unfettered by and untethered to the idea that someone out there must have the answer.

Finally there was an original insight or two, which still hasn’t been given what philosophers call a “fair and sympathetic hearing.” The resolution to the riddle is elegant in its simplicity.

Wherever life evolves the neuronal complexity sufficient for a creature to break the bonds on niche, through the adaptive strategy of ‘higher thought’ enabling conscious manipulation of the environment, there is a strong tendency to mistake the ability to cognitively separate for the way nature and the universe actually work.

Our alienation from nature, our tribalistic natures, our wars and genocides, our gross economic disparity, and our increasing fragmentation of the earth all have their roots in this ongoing mistake. I have done away with ‘original sin,’ and all the claptrap of Christianity; human division has its roots in the evolution of so-called higher thought.

That doesn’t absolve us (pardon pun) from responsibility. On the contrary, the fault, though initially in our stars, is enduringly within us. It will be resolved when living generations have sufficient insight into the nature and operation of thought to liberate the individual and humankind from its thrall.

A new question has arisen in recent months, one that remains a Gordian knot awaiting a swift, clean cut of insight. Why, if the evolution of brains like ours is the intrinsic intent of the universe (brains with the potential to consciously commune with the awareness that infuses the universe), is it so difficult and rare for the human being to attain that awareness?

Any hint of teleology is verboten in science and philosophy. Increasing complexity, and directionality driven by randomness, cannot be denied however.

Life is either inevitable in cosmic evolution, or it is unique on this planet. Since the latter is an untenable position, the question is: Does life, given the right conditions and enough time, inexorably evolve creatures with increasingly complex neuronal systems, which at some point are able to consciously separate, manipulate and accrue knowledge about their environments and the universe?

Creatures like man may not be so rare. But since psychological and ecological fragmentation strongly tends to accompany the evolution of symbolic thought, with its propensity for division and fragmentation, there are a finite number of chances to change course before destroying the very ground on which all creatures depend.

We are part of nature—indeed, we are the cosmos aware of itself—when thought is completely quiet. Of course, thought is rarely completely quiet. And at this evolutionary stage, thought thoroughly dominates the human brain.

In the past, when humans lived close to nature, or when tradition still had some coherent and cohesive force, symbolic thought was not such a problem. Now, rather than finally take the age-old remedy of self-knowing, most smart people ludicrously believe that science and technology will save us.

When thought falls silent through passive watchfulness igniting undirected attention, the human brain is sensitive to pure reality—actuality. Again however, why is that so difficult and rare?

Martin LeFevre