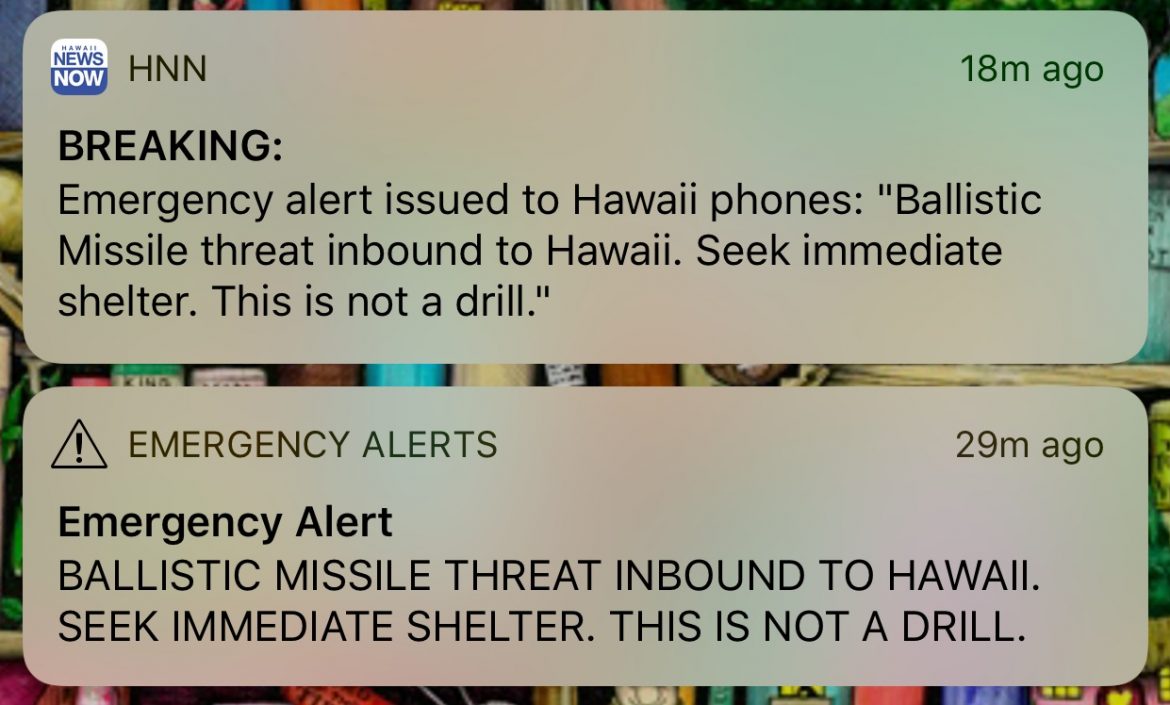

“This Is Not A Drill.” No, it’s not. This is what chaos feels like. The fact that so many people ran for their lives in terror in Hawaii on Saturday at a mistaken nuclear missile alert attests to how volatile the world is.

While nation-states play their deadly games, and “the sole remaining superpower” descends to the level of reality TV (except that the adolescent in the White House is playing with nukes), the question becomes, what are ordinary human beings to do?

In talking with citizens, religious leaders and activists from different countries recently, I perceive three reactions and one response.

The first and most common reaction is to continue to stick one’s head in the sand, focusing on immediate personal needs and pleasures. Underlying this reaction is the worldview, ‘I don’t have anything to do with it, and can’t do anything about it.’ The logical result is the attitude, ‘give up and hope the end comes quickly.’

The second reaction is to continue to play the politicians, media and academic’s game, and indulge in endless discussions of how to confront North Korea (or Russia, or China, or Iran, or…) and whether to “rebuild our military” (along with bomb shelters), and prepare for the fallout, literally and metaphorically.

The second reaction is to continue to play the politicians, media and academic’s game, and indulge in endless discussions of how to confront North Korea (or Russia, or China, or Iran, or…) and whether to “rebuild our military” (along with bomb shelters), and prepare for the fallout, literally and metaphorically.The third reaction, the default position of progressives in America, is to keep telling yourself you’re preventing the unthinkable from happening, even as the US military conducts preparations and exercises for war.

(As was reported this morning, “unlike the very public buildup of forces in the run-up to the 1991 Persian Gulf war and the 2003 Iraq war, which sought to pressure President Saddam Hussein of Iraq into a diplomatic settlement, the Pentagon is seeking to avoid making public all its preparations for fear of inadvertently provoking a response by Mr. Kim, North Korea’s leader.”)

The ‘all we can do is try to prevent war’ mindset was expressed to me recently by the convener of religious leaders of all faiths from around the world for another talk-shop conference. This one, in Costa Rica, is entitled “The Dawn of InterSpirituality in Latin America.”

“Perhaps my conviction that this disaster can be turned around is a pipe dream, or an enabling illusion,” Dr. William Keepin wrote, “but I still stand by it, because until we actually utterly fail, there is still a chance of success, however slim, and I plant my stakes there.”

That echoes the glib comment that President Obama uttered to his devastated and tearful staff the morning after the most unfit man in the history of the American presidency was elected to office.

In a White House that was “like a funeral home,” as a staffer was quoted as saying, Barack Obama was his same preternaturally cerebral self: “I don’t believe in apocalyptic — until the apocalypse comes. I think nothing is the end of the world until the end of the world.”

That’s not just slick, circular thinking; it’s the vicious circle that characterized Obama’s presidency. It means changing nothing, merely continuing to plug away in the status quo, even after the status quo is dead and gone.

As I said to Dr. Keepin, the self-comforting idea of a “transformative possibility of humanity as a likely future reality” is precisely what keeps “the forces of darkness and ignorance” in charge in the present. That approach has been taken for thousands of years, and it is a prescription for humanity’s failure.

So what is the fourth possibility? It is to respond rather than react. To understand the difference, it’s necessary to deal with the anxiety that now permeates human consciousness.

To my mind there are two kinds of anxiety. The first is self-generated, coming from childhood trauma, conditioning, worry, etc. The second is a reaction to external conditions, the anxiety we all now feel after Trump and the Republican’s pathological deconstruction and destruction of reality, and the terror in Hawaii .

Anxiety, whether internally generated or reactive to externalities (including the presence of evil), means: Take heed; pause; attend; redirect.

We may not be able to prevent the ‘unthinkable,’ but we can respond intelligently in the present.

Martin LeFevre