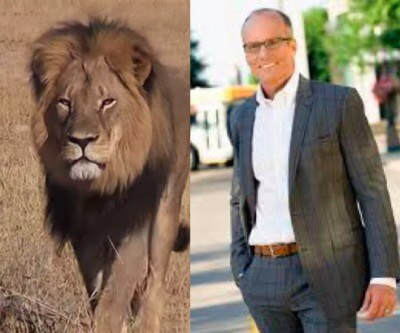

Today is World Lion Day. The big-money pleasure killing of a Zimbabwean lion named Cecil is being portrayed in the New York Times as humans vs. nature, romanticism vs. reality. It’s neither.

Unfortunately, the killing of a radio-collared lion in Zimbabwe by an American dentist from Minnesota has gotten more media coverage than the deaths of innumerable Africans from man-made violence over the past decade.

Unfortunately, the killing of a radio-collared lion in Zimbabwe by an American dentist from Minnesota has gotten more media coverage than the deaths of innumerable Africans from man-made violence over the past decade.

On one side is the virtual lynch mob in America calling for dismembering the dentist the way he dismembered the reportedly beloved lion who lived in Hwange National Park.

On the other side is the supposed ‘truthbomb’ dropped by a Zimbabwean in America who says of the eruption of American sentimentality: “I faced the starkest cultural contradiction I’d experienced during my five years studying in the United States.

Nothing illustrates the pathos of culture clash, and the illusion of identification with countries in the global society than that statement.

And nothing illustrates how pathetic a proprietary attitude toward apex animals is, especially the dwindling species of great fauna in Africa, than the attitude evinced by the same writer: “Don’t tell us what to do with our animals.”

Pulling at a different set of heartstrings, the writer tells of children being killed by lions, strumming the old, fear-the-wilderness trope by saying, “In my village in Zimbabwe, surrounded by wildlife conservation areas, no lion has ever been beloved, or granted an affectionate nickname. They are objects of terror.”

Were lions “objects” of terror prior to colonial times, or were they feared and respected as an integral part of the land? Taking this attitude, it’s a small backward step to the days of the “Dark Continent” being saved by the great white hunter, and a small stumble to a future where lions are either exterminated or caged in large zoos for drive-by tourists.

I have no sympathy for naming animals and giving them romantic roles in human morality plays. But there is something unseemly about a Zimbabwean, after gaining all the material benefits the United States has to offer, lecturing Americans: “Don’t tell us what to do with our animals when you allowed your own mountain lions to be hunted to near extinction in the eastern United States.”

If the world is actually divided into nations and continents, with each people having to learn their own lessons separately from the rest of humanity, then such an attitude makes perverse sense. But since colonial times, as brutally disruptive of African peoples and cultures as they were, Africa’s fate has been inextricably entwined with the fate of humanity as a whole.

Do Africa’s national resources belong to the people of those countries? Do the Grand Canyon and Yosemite belong to America, or are they part of the earth for all people? Isn’t the very concept of ‘national resources’ a Western one, a concept that has been misappropriated by China, which seems to be buying up the entire Continent?

Paleo-anthropologists say that both ancient and modern humans evolved in Africa. People lived in Africa for thousands, indeed hundreds of  thousands of years before Europeans ‘discovered’ the Continent. And pre-colonial peoples, comprising an incomprehensible panoply of cultures, languages and traditions, survived and thrived without the help of Western technology and concepts of ownership.

thousands of years before Europeans ‘discovered’ the Continent. And pre-colonial peoples, comprising an incomprehensible panoply of cultures, languages and traditions, survived and thrived without the help of Western technology and concepts of ownership.

So it’s very disturbing to hear an African in America say, “The village boy inside me instinctively cheered: One lion fewer to menace families like mine.” Did his ancestors, for whom “wild animals have near-mystical significance,” feel that way when a lion was killed?

Or did this magnificent animal test human strength, bravery and cunning to its limits, and so was held in the highest regard by African hunters who slew lions armed with only spears and arrows?

Nowhere in this New York Times opinion piece by Goodwell Nzou is the destructive encroachment of humans on the magnificent animals of Africa mentioned. Nowhere is poaching mentioned, or the corrupting influence of big-game hunting, which brings in huge amounts of money that benefits ordinary people very little, and benefits declining populations of animals like lions, elephants and rhinos not at all.

To be sure, the immense challenges of preserving what remains of the last great herds and predators, which exist nowhere on earth like Africa, is primarily an African responsibility. But the urgency of redressing the growing imbalance with nature must involve every person on the planet who cares about the fate of the planet and humanity.

Western constructs of nation and ownership of animals, epitomized by sick American dentists or confused African expatriates, can no longer prevail over the unsentimental and non-romantic perception and passion of human beings everywhere.

There are about 20,000 lions left, down from about 200,000 just a few decades ago. The future of humanity turns on the relationship between people and animals in every ocean and on every continent, beginning with Africa, where we all began.

Martin LeFevre

Link: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/05/opinion/in-zimbabwe-we-dont-cry-for-lions.html