It was the beginning of the last full year of the USSR, when St. Petersburg was still named after Lenin. As dusk deepened in the unlit palace museum where Rasputin was murdered, a cultural director gave me a vivid, step-by-step walk through his poisoning, shooting, beating and finally drowning in the ice-choked Neva River.

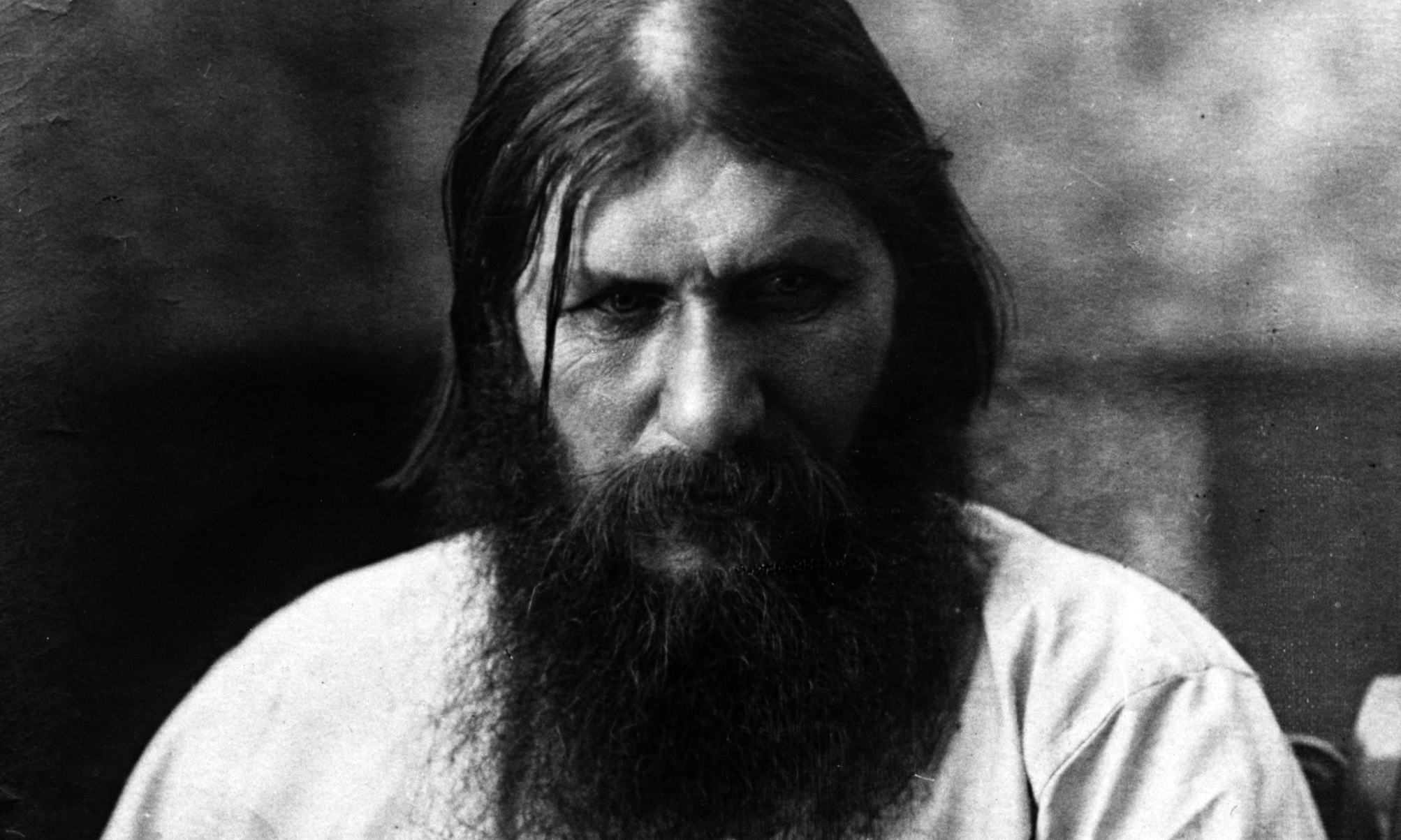

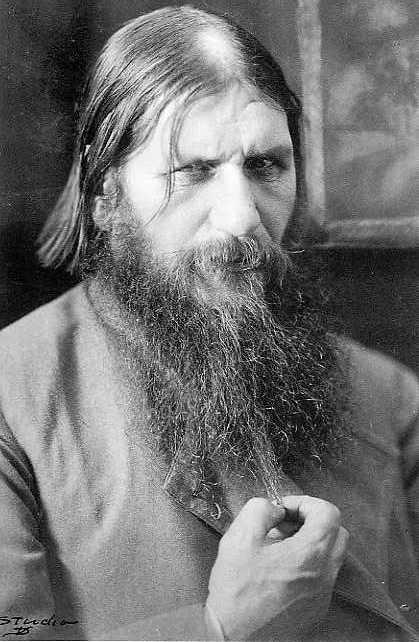

As a young man, I had a fascination with Rasputin, the Russian mystic who held the Romanovs in his thrall because he could stop the bleeding of their hemophiliac son. He is the quintessential mystic gone wrong.

As a young man, I had a fascination with Rasputin, the Russian mystic who held the Romanovs in his thrall because he could stop the bleeding of their hemophiliac son. He is the quintessential mystic gone wrong.

Shortly before my trip to Russia that January, as the glacial relations of the Cold War thawed, and a friendship between America and Russia seemed not only possible but plausible, I had a memorable conversation with a friend, poet and literature teacher.

I don’t recall what Brian’s Master’s thesis was, nor any line from any poem he wrote. But a stunning remark he made in a conversation we had about Dostoyevsky, one of the greatest Russian writers and perhaps the grimmest chronicler of human nature, really stuck. With a glinting, unemotional tone that sometimes came over him, Brian said, “I had friend who read all the works of Dostoyevsky one year. Then he killed himself.”

Having read enough Dostoyevsky in my depressed youth to understand how that could happen, I remember thinking, so much for the whole Great Books/Big Ideas thing. That’s the idea that ‘you have to grapple with the big ideas and the big books that teach you how to experience life in all its richness and make subtle moral and emotional judgments.’

That ideal was all but history a quarter century ago; now it reads like ancient history. But the ideal of the ‘still perfection of art’ hangs on, as well as the notion that knowledge and wisdom go hand in hand.

After my Leningrad host had reenacted, in the gloomy twilight of the USSR, Rasputin’s gruesome murder in the nobleman’s palace, we met with a group of the city’s cultural elite. Though I didn’t speak the language, it felt like I was among old friends. We talked long into the night. There were no other Americans in the city I knew of, much less any who had come in friendship to see if former superpower enemies could forge a new way ahead.

I hadn’t believed in reincarnation before visiting St. Petersburg. But from the moment I entered the city, I was sure I’d lived there before. Now I realize, as the saying goes, “reincarnation is a fact, but not the truth.”

We discussed Rasputin and religion of course, as well as the Communist Revolution that came on the heels of the demise of Tsarist Russia. My Russian friends talked with tremendous passion about the communist system. Everywhere I went there was a simmering, collective anger. “They are stealing our lives!” one young man shouted.

Our bond was not in literature, or even ideas, but rather in mutual exploration at a hinge of history. We talked how we, Americans and Russians, had brought the world to the brink of nuclear annihilation. Yet here we were, trying to find a way ahead together. The discussion, far ranging and in-depth, was translated through my extraordinarily capable interpreter (so capable I forgot she was there that night, for which I apologized later). At the end of it, I said: This city will be St. Petersburg again within the year.

They looked at me in stunned silence. They knew full well what I was saying; I dared speak what they dared not hope—that Communism would soon be finished. But it was not a drunken boast, rather a sober certainty—the same certainty of prediction though failure of prophecy that brought me to Russia. (I visited Leningrad in January 1990; the city became St. Petersburg in November of that year. The USSR ended the following fall, and the US began calling itself ‘the sole remaining superpower.’)

My mother, who came as close to being a John Bircher as an American could without being a card-carrying member of that rabidly anti-communist organization, had often said growing up, “when the Russians finally throw off the chains of communism, we Americans will be there to help them.”

Living in Silicon Valley in the late 1980’s, I had the opportunity and contacts to act on that false promise. To my surprise, the Russians seemed to have heard the same line, perhaps because of Herbert Hoover’s (yes, that Herbert Hoover) food relief campaign during the darkest days under Lenin, which saved many thousands of Russians from starvation. The Russians, having long historical memories, unlike we Americans who have none, believed I was the beginning of a wave of Americans that would be coming to help them build a new market, and begin to fill the empty shelves and lives of the State control.

But there was no support. As Robert Reich, the incoming Secretary of Labor in the first Clinton Administration, wrote to me at the time, ‘we’re going to go global rather than bilateral.’ That meant China more than Russia. We’ll rue the day that decision was made.

It’s wishful thinking in the extreme to hope that ‘humanity’s inherited storehouse of moral, emotional and existential wisdom’ will light the way out of the morass in which we find ourselves.

Humankind has amassed tremendous knowledge, both in science and the humanities. There have been periods of great artistic and intellectual flowering, which continue to inspire. But these two streams—knowledge and art—have not led to wisdom. On the contrary, darkness engulfs the world, and it seems Homo sapiens in inwardly devolving, not evolving.

The way ahead is at it has always been—not by through knowledge or even art, but through the spadework of self-knowing and questioning. Wisdom flows from insight and understanding, which are always of the present, not from knowledge and art, which rightly have their roots in the past.

Beyond memory, I hope my Russian friends retain something of our communion that wintry night, for we are in even more uncharted territory, and again the low drumbeats of war have begun, echoing over the entire world.

Martin LeFevre

http://www.damninteresting.com/retired/the-death-of-grigory-rasputin/