After a light all-night rain, the clouds cleared and the sun made a welcome appearance in the early afternoon. People got outside and into the parkland in droves, including me. Meditation was just igniting through undivided, undirected observation when a rollicking group of boys descended on my sitting place.

They all wore the same orange striped shirt, and none saw me sitting on the other side of a tree as they ran down the bank. Their father (he seemed rather old to be their father but one of the four called him Dad) looked down from above. “There’s a man fishin,’” he said. ‘Not fishin’, I replied. “Wishin’ then,” the man retorted. Not that either, I thought.

They all wore the same orange striped shirt, and none saw me sitting on the other side of a tree as they ran down the bank. Their father (he seemed rather old to be their father but one of the four called him Dad) looked down from above. “There’s a man fishin,’” he said. ‘Not fishin’, I replied. “Wishin’ then,” the man retorted. Not that either, I thought.

One of the boys came around the tree and stood next to me in a quiet, friendly way. He was about seven, and had a wide-eyed, innocent face. ‘Why are you all wearing the same shirt, are you brothers?’ I asked. He smiled, as if he’d been asked this question many times, and just said something about “looking for oak balls.”

‘Oh I know what you mean,’ I replied, and it occurred to me that they could well be quadruplets, since they all looked the same age. The boys had obviously thrown the fungal spores, which grow in large numbers on the plentiful oaks in the park, into the creek upstream, and had run downstream to watch them float by.

In the meditative state, there was no distance between the boy and oneself, and indeed, it seemed almost as though I was looking at myself. It wasn’t just that he reminded me of myself as a boy, but that in one sense, he was me.

Without self-knowing, the grooves of conditioning in childhood become well-worn ruts as we age. Children under seven or so don’t have the barriers of fixed identity. They could be shown how to observe in a way that keeps their brains young and insights flowing even into old age.

How could that be done? Simply put, if the adults caring for children were self-knowing, and deepening their capacity for undivided attention, children would learn from an early age how to observe. Then conditioning would not take root in their minds and hearts, at least not so deeply.

Very few adults are self-knowing however, and many don’t even see the value of being so at all. I read something recently that explains why that is: “Meditation is a danger to those who wish to lead a superficial life.”

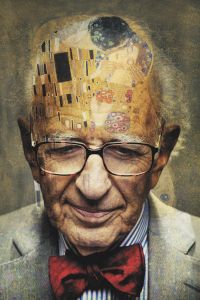

Even Nobel Laureates overvalue memory and give it primacy, such as Eric Kandel in his book, “In Search of  Memory.” Kandel says that he would “like to develop a reductionist approach to the problem of attention.” He reflexively links his question, “what is the nature of the spotlight of attention?” with “the encoding of memory throughout the neural circuitry.” For Kandel, “selective attention is one of the royal roads to consciousness” because it encodes and seals memory.

Memory.” Kandel says that he would “like to develop a reductionist approach to the problem of attention.” He reflexively links his question, “what is the nature of the spotlight of attention?” with “the encoding of memory throughout the neural circuitry.” For Kandel, “selective attention is one of the royal roads to consciousness” because it encodes and seals memory.

But that’s false and wrongheaded. When he speaks of “selective attention,” Kandel is really talking about concentration. Attention is a completely different and distinct phenomenon.

Concentration does indeed “encode memory,” whereas attention creates space in the mind, quiets thought, and deletes unnecessary memory. And erasing memory is far more important than encoding it, because most memories are not just unnecessary, they are harmful to healthy brains and healthy relationships.

On the other hand, inclusive and undirected attention without a center as the observer is the essential action that awakens meditation and higher states of consciousness.

The brain automatically records and accumulates experience as memory, perhaps nearly all experience. Of course not all memory is consciously available. That’s the heart of the problem; most people act out of a vast unseen swamp of mental and emotional memory, the tar-like residue of conditioning from family, culture and ethnic group.

A human being, on the other hand, is essentially free from conditioning and psychological memory. And to be free from conditioning, one must be able to delete divisive and useless memory. That doesn’t happen through any action of effort or will, but only through passive observation gathering tremendous energy of attention. Attention then acts; the self doesn’t.

Discerning which memories to delete and which to keep is therefore not an act of conscious choice, but of the intelligence of awareness. Observing the movement of the mind and emotion, the spurious barrier between the conscious and unconscious mind dissolves, and the entire movement of thought and emotion reveals itself. Attention then grows and is self-sustaining (at least while sitting still), and the mind/brain effortlessly lets go of everything and falls silent.

With complete stillness of the content and mechanisms of thought, the brain is renewed. Rather than its synapses tunneling in the same old ruts, one is liberated from the deepening grooves of memory and habits of thought.

The mind and brain, in letting go of psychological memory, has the space and energy to see and create anew. This is what we have to learn within ourselves, and teach children.

Martin LeFevre