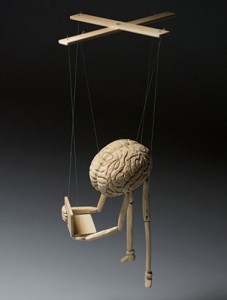

Do children need to be conditioned? Human conditioning is taken as a given, unquestioned as much as the sun rising in the morning. But conditioning is enslavement, not an immutable factor of the human condition, as most people assume.

Though I have no children of my own (an injunction or compunction, an invective or introspective) I have been fortunate enough to be with young children in different capacities.

Though I have no children of my own (an injunction or compunction, an invective or introspective) I have been fortunate enough to be with young children in different capacities.

Many years ago I had an insight into conditioning while taking care of one little fellow between three and four years of age. I observed, to my consternation, that he had no awareness or fear of cars. After restraining and chastising him a few times over several occasions, I questioned what to do. I couldn’t resort to the usual parental reaction of a whack on his behind, since, besides not being his father, I didn’t believe in hitting children.

Attending carefully to him and myself (the latter is the essential) while we were out, I simply watched and waited, without an idea of what I would do but with the intent to somehow show him, once and for all, that cars were extremely dangerous.

As he began to obliviously step off the curb the next time, I instantly saw what to do and acted without the usual gap between idea and action. I dropped down to his level, grabbed him by the shoulders, and through look, gesture and voice conveyed the danger of the situation as I was feeling it. I wasn’t reacting; there was simply total response to the danger in the present, and the direct communication of it.

It scared him, but in the correct way. Fear of physical danger is intelligent; psychological fear, the basis of conditioning, is what is false and destructive.

Because there was a relationship of attention, affection and care, the direct perception of danger was conveyed to the little boy. He didn’t have to be told again, by me or anyone else, to be careful crossing the street. Conditioning, much less violence, was not involved.

I realized that even with something as imperative as teaching a child the danger of crossing a street, a parent, teacher, or caregiver need not resort to coercion and conditioning.

or caregiver need not resort to coercion and conditioning.

Conditioning involves violence in some form, through coercion and imposition. Even with imitation, since when we try to be like someone else, we do violence to ourselves. Conditioning leaves a trace, a mark in the mind and heart, whereas learning through direct perception and insight leaves no marks and establishes no grooves in the brain.

Therefore we’re talking about a completely different kind of learning, based not on imprinting knowledge and experience, but on awakening insight and illumination. Can that be taught to children? No, but a self-knowing adult, attentively awakening insight within them, can convey insight to the children in their charge.

A complete human being can be defined as a person liberated from conditioning. We need to at least be moving in that direction, rather than continuing on the old, dead-ending course of conditioning.

So whether one uses synonyms for conditioning with negative connotations, like taming and breaking; or words with neutral connotations like socialization and training; or with positive implications like teaching and preparing, there’s another way altogether for children to develop than to condition them. But adults first have to be un-conditioning themselves.

The beginner’s mind is not just for beginners. The term doesn’t refer to people who are beginning to awaken, or just starting out in meditation.

It refers to the realization that however deeply a person awakens, however illumined one may become (which isn’t a matter of becoming at all), the experiencing of insight, wholeness and holiness is always a matter of beginning. Meditation is in one sense the un-conditioning of the brain, allowing the growth of the heart, and the vastness of mind beyond thought.

Conditioning is not just the patterns of childhood, brutally imposed or carefully impressed upon us when we’re young. It’s also the habits of adulthood, mindlessly and accumulatively overlaid upon childhood’s substratum of unawareness. The totality of conditioning makes for the grooves of the self, which, through inattention and lack of daily spadework, inevitably become the ruts of older age.

It boils down to the place we give knowledge and experience, as contrasted with awareness and insight. If the former is first, as it almost always is, then conditioning in some form is unavoidable. But if we put insight and understanding before knowledge and experience, development has a very different meaning.

It boils down to the place we give knowledge and experience, as contrasted with awareness and insight. If the former is first, as it almost always is, then conditioning in some form is unavoidable. But if we put insight and understanding before knowledge and experience, development has a very different meaning.

Most parents and teachers believe their first responsibility is to train children how to successfully compete in the economy. But making that primary ignores the kind of society we want to have, much less the kind of human beings we want to raise.

Giving attention to these questions creates clarity of intent and action. Rather than increasing the burden on overburdened parents and teachers, as most people think (‘I don’t have time for that,’ though there’s plenty of time for every other bit of nonsense), reflecting on the whole person in the context of society lessens one’s burden and fosters freedom.

Ending conditioning within oneself is not a matter of analysis and reason, but of undivided observation and undirected attention. When one becomes aware of a pattern or program, just watch and remain with it. Don’t do anything or try to control it. Don’t judge or even evaluate it. Just hold still and observe it inclusively for a few seconds at least.

Then you’ll see that the conditioned programs–the chains that shackle us within–loosen their grip and dissolve. Beginning that journey anew each day, parents and teachers will raise children in freedom.

Martin LeFevre